[Contains mild spoilers]

The Defiant Ones (1958) – Sound/Score

I’ll be a bit twatty for a sec and say there’s nothing quite like watching a film on literal film. The crackled imperfections just hit in a way smoothed over digital releases don’t for me. Which is why I try to go to indie cinemas a couple times a year to both scratch that itch and support 35mm funds. In London, it was The Prince Charles Cinema, and now Boston’s Brattle Theater and Coolidge Corner Theater. And it just so happens the Coolidge has some excellent programming on right now, so this week and next, we’re doing films from the Coolidge.

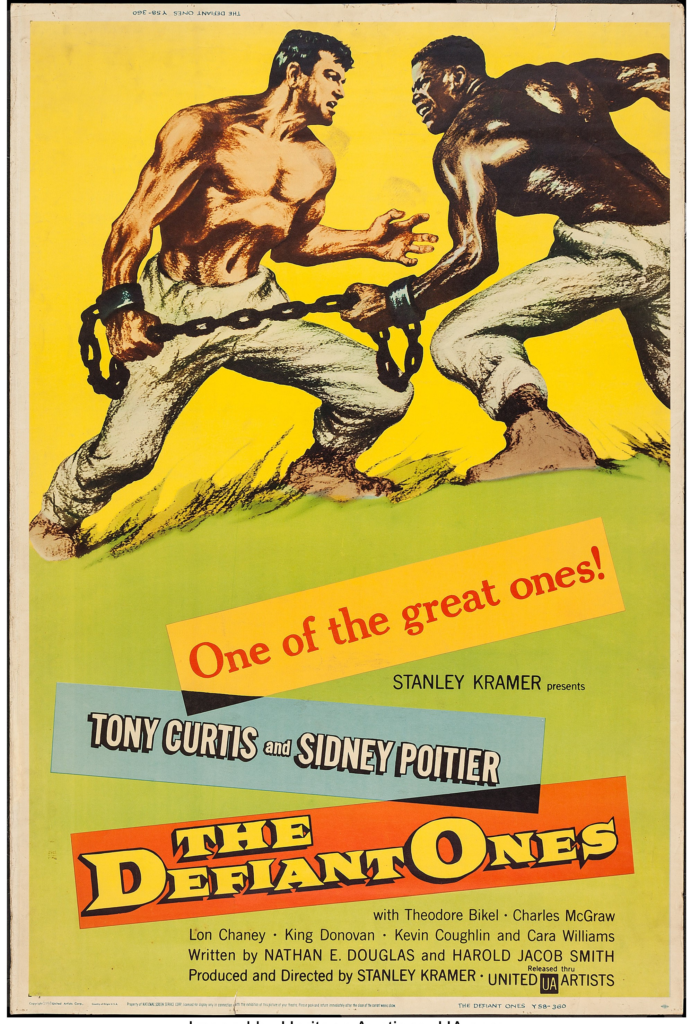

Up first is Stanley Kramer’s The Defiant Ones (1958) starring Tony Curtis and Sidney Poitier as two escape convicts, chained together and forced to rely on one another despite racial tensions and realities of the Jim Crow South. The Review Roulette wheel landed on Sound/Score for our approach, and I was a bit nervous, never having seen the film before, but there is a fascinating use of sounds that does indeed deserve some musing.

So, the two ex-cons are on the run having escaped from an overturned prison transport. We’re told that the black and white men were chained together because the warden has a sense of humor about violent racism, setting up the outstanding acting performances by Poitier and Curtis. As one would expect, the two form a sort of friendship by the end of the film, with Curtis realizing that his racist assumptions about Poitier are not only unfounded but actively harmful to someone he comes to see as a man in his own right and Poitier making the 3-dimensional case for race and class solidarity between the two. Ultimately, both make sacrifices of happiness and freedom for the other.

However, before we get to that beautiful, hard-won ending, we have their first real dialogue-heavy scene together on their first night on the lam. As the two devour a frog they killed and cooked together, they have a conversation about the animals they can hear in the swamp. Sounds of bugs chirping in the wild prompt Curtis to ask what animals are around them. Poitier says there are gators, wild pigs, and black bears. Curtis, visibly freaking out, asks why they don’t make any sound, and Poitier says that they’re just animals, they’re either being hunted or hunting. Curtis muses romantically on the idea of silence while simultaneously idealizing the sounds of the bugs, saying, “Must be a million of ‘em. Not one of ‘em understands what the other one is sayin’… Bugs or people. Nobody understands anybody. Them animals, they’re smarter. You keep quiet and you hunt for yourself.” (During this freshman year philosophical roll, Poitier is just eating his frog meat with a “this fuckin guy” face, saying “they just bugs”.)

Eventually, we hear a weasel’s distraught squeal and an owl’s hoot. Poitier explains that the only time animals make noise is when they’re dying. Curtis says wistfully that that is the way to live, “you keep quiet all your life, and the only time you open your mouth is when you’re dyin’.” This conversation is immediately followed by a bit of a heavy-handed parallel with their own places in society.

But I think this use of sounds is really beautiful and also leans into the main theme of the film and also a subtler one. The main theme is the opposite of Curtis’s philosophizing: that if we listened to each other more and took the time to understand each other better, society would be much better, and keeping quiet is how we fail each other. It’s a film about solidarity and the evils of racism.

That heavy-handed parallel is in the follow-up character-establishing conversation about their places in society. Curtis talks about his dreams of being a wealthy man one day, one who can walk on others as he feels he had been walked over, forced to say “yes, sir” and “thank you, sir” when he worked as a valet for a fancy hotel. Because of this job, he hates saying “thank you” to anyone, arguing it makes him feel lesser. Which is a ludicrous opinion, but it establishes that he is in the low working class and has always at least felt as though he was on his own against the world.

In complaining about the phrase “thank you,” Curtis says the words just stick needles in him every time, adding, “That can happen with a word. You know what I mean, boy?” Poitier gives him the exact look you’re imagining and points out the irony of his prejudice, both with his use of “boy” and the n-word that Curtis had called him earlier. Poitier also points out that neither of them will ever be invited into that fancy hotel, subtextually arguing that the two escaped convicts are closer to one another in social status than Curtis is to a wealthy white man. Curtis rebukes this idea as simply following the rules of society, and Poitier likens him to the weasel killed by the owl. “You callin’ me a weasel?” “No. I’m callin’ you a white man.”

The use of animal sounds, imagery, and metaphor add up to a solid vehicle for their two points of view: Curtis’s isolationism and Poitier’s subtle collectivism. You can be silent all you want, but that owl is still going to get your ass. Complicated metaphor for each to argue for the “natural order of things” in defense of their own angry outlooks. Check!

But, I think the animal sounds also emphasize another, more surprising layer of the film. While the men are on the run, they are also being chased by a sheriff, his deputized losers, and a pack of wonderful bloodhounds. The bloodhounds get close ups and jaunty music to break tension in the film but also, I think to take them out of it a bit. The film has this rather remarkable stance about animals that they are not lesser, and the dogs don’t know they’re tracking escaped cons; they’re just following scents. So they get this delightful soundtrack, and they also get an owner who loves them dearly. He defends them, argues for rest on their behalf, and simply adores these dogs.

And I think that balance is incredibly important. We have this story of men treated as less than human, men who muse on the wild animals around them. And then we have these dogs who are treated better than anyone else in the film. And I think this animal theme really suggests an inherent equality in nature between man and animal. There’s no dehumanizing/animalizing if we respect all living beings as part of the natural world. And this is symbolized through the final sounds of the film when Poitier sings loudly as the two are found. Having been silent to their hunters (animal and man) the whole movie, the pair only open their mouths when they’re caught.

I think this idea of the sounds of animals and the treatment of them is very well-crafted and, as I said, a genuine surprise in the film. The dogs’ owner is so enamored with his dogs in a way that’s comical to the law enforcement present, but his willingness to treat his animals with respect, dignity, and love is the whole point. And I think that’s beautiful. There is no lesser if we fix our hearts. There is no immutable rule of society if we dare to love one another. As Bad Bunny reminded us just a few days ago, the only thing more powerful than hate is love, and that extends to all living beings.

Leave a Reply to Jamie Christman Cancel reply