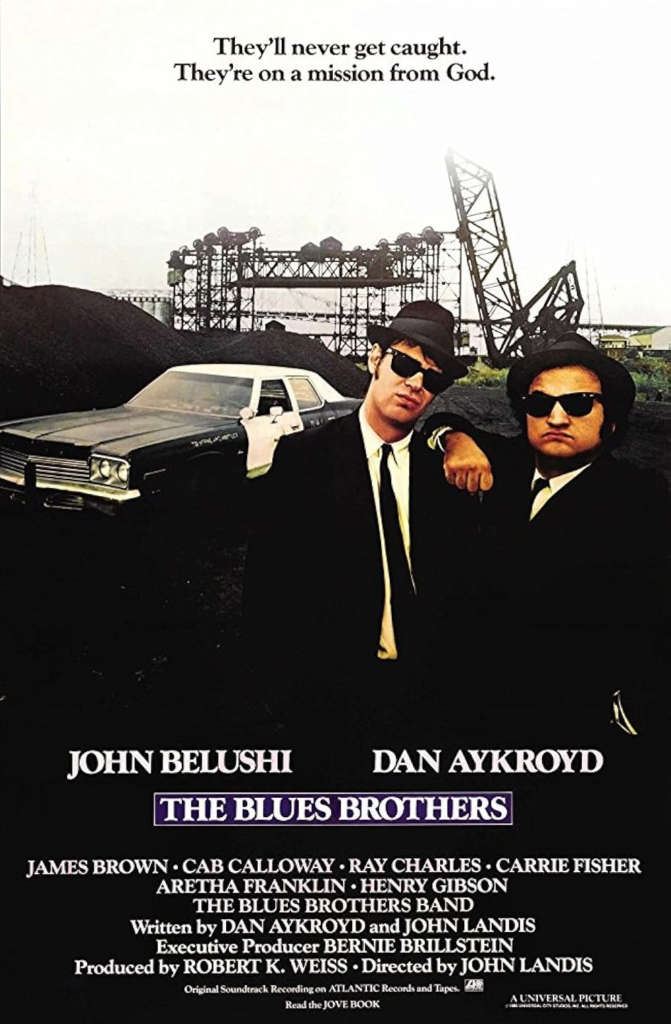

An Apparatus Approach to The Blues Brothers (1980)

The Blues Brothers (1980) – Apparatus

This week, in honor of our cowardly president being rightfully afraid of Chicago, we’re celebrating the 45th anniversary of one of my favorite films, The Blues Brothers (1980), so get the bullwhip ready and count the horns section down because we, we right here? We’re on a mission from God.

You know how some kids have security blanket kinds of movies? Mine were *not* normal as a child in the 2000s. Like Mel Gibson’s The Patriot (2000) was my sick movie. When I stayed home from school at like 7 years old, I was having my little juice and crackers and putting on Mel Gibson’s The Patriot for comfort like a FREAK. Well, The Blues Brothers was also one that I was just obsessed with. Cab Calloway’s rendition of “Minnie the Moocher” was one of the first songs on my iPod Nano. I was listening to the Blue Brothers’s version of “Soul Man” before I knew what soul was (in the musical and metaphysical senses). Aretha Franklin singing “Think” in this film introduced me to her highness, the Queen of Soul. What a GIFT this movie is, truly.

And that’s what we’re going to talk about this week. The Review Roulette wheel landed on Apparatus as our approach, that is, we’re going to analyze how the film portrays or interacts with structures of society, and because I am not normal and am, in fact, an aforementioned freak, the structure we’re going to look at is culture through its interaction with time. Let’s get 3D spacetime in here to talk about The Blues Brothers, why not?

So, The Blue Brothers band started on Saturday Night Live as kind of a joke, but mostly an excuse for Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi to fulfil a joint dream of being blues musicians. They were comedians first and foremost, but they also had this deep love for the blues that manifested as an homage to the most American music tradition and its artists. And they fought for the ability to honor it in the 1980 film.

For those unfamiliar, obviously go watch it. It leaves Netflix at the end of September, so if you have that service, go watch it and bask in its musical baptism. But if you want to finish reading this first, it’s about Jake and Elwood Blues (Belushi and Aykroyd) on a mission from God to procure $5000 to save the Roman Catholic orphanage where they were raised (and baptized in blues by Cab Calloway). After hearing a sermon by James Brown, Jake sees the light and decides they need to put the band back together, leading them on a musical journey on which they gather a litany of enemies in the wake of many, many crimes (mostly car-based) before securing the money at a blues revue.

There are two things I want to talk about here. Firstly, because I have just spent 5+ years studying midcentury Christmas films for my PhD and new book (Selling Out Santa: Hollywood Christmas Films in the Age of McCarthy), it dawned on me that The Blues Brothers has the same prompt as White Christmas (1954). In both films, a musical duet is informed that a person of great significance to them is on the verge of losing their livelihood due to financial pressures. The duets decide to host a revue to raise the money and save the day. There are fascinating differences such as the places of significance being an orphanage in The Blues Brothers and a Vermont inn in White Christmas – or the very, very different approaches to remembering black music traditions (the minstrel number in White Christmas for instance) – but the similarities are also striking. Which leads us to the second thing: nostalgia.

If we think of The Blues Brothers as a film in a genre of American nostalgia films with White Christmas (we’re allowed to be loosey goosey with genre, even if it’s just these two films, stick with me), then we can see a really interesting structure start to take form. Between these two films we see a need for a younger generation to save the present by reaching into the past and bringing elements of American culture forward. They use these icons in our collective nostalgia to improve the present (a phrase that feels gross to type in 2025, but really is politically neutral!).

White Christmas invokes minstrelsy to ground its variety show in a musical tradition while having numbers like “Choreography” which questions why everything now has to be choreographed, implying an earlier tradition of dance was preferable to the trend in contemporary music and dance. That critique of the how of song and dance is a metaphor for the film’s larger critique of the US military in Korea: it uses many musical numbers and settings and characters to establish a deep nostalgia for the military of WWII while condemning the direction it has taken since in its rejection of one of the main characters’ bid for reenlistment. The film reaches backwards to comment on and rescue the present by embracing nostalgia over contemporary reality.

The Blues Brothers invokes specific blues music that was mostly released in the late 50s, early 60s but also a few that stretch back to the 30s and 40s. It reaches backwards to rescue the present in an even richer way than White Christmas because of the conditions of the present. The orphanage is home to a diverse group of boys in Calumet City, Illinois and overseen by a white nun and a black caretaker, Curtis (Calloway). The church has decided to turn the home over to the Board of Education rather than pay their taxes. Curtis says that he will be turned out on the street because “What’s one more old n— to the Board of Education?”

When laying out the stakes of the orphanage’s closure, the film injects this bit of reality that the Board of Education is historically at best indifferent to black American communities and individuals. The film’s response to that recognition is to reach back and pull forward these iconic American musicians and rightfully highlight them as the voices of the mid-20th century. It says that the BoE’s indifference is reality but so the fuck is the importance of black musicians to our culture. Curtis’s influence on the boys alone is enough to confront the BoE as an alternative education, one rooted in American cultural history, but the film goes beyond that.

When film execs at Universal balked at the idea of having James Brown, Aretha Franklin, and Cab Calloway on the basis that none had a hit in years, Aykroyd fought for their inclusion. Execs wanted to freshen up the taste with younger, more contemporary acts like disco’s Rose Royce, but Aykroyd defended the nostalgic ideal of these blues and soul legends as the heart of the film. The conversation doesn’t work as well with contemporary music; saving the present required an embrace of tradition.

And you know who agreed? The Library of Congress when they added The Blues Brothers to the National Film Registry. Not only is it an excellent comedy with a heart of using our best American traditions to fight our worst, but it’s also a treasure trove of footage of those blues greats, an archive of cultural history.

Man, go watch The Blues Brothers. I’m about to go watch it again, I love this movie so much. This movie says “the only way out of racist, systemic bullshit is through setting the culture right” and that is a lesson I have been banging my drum about for years. Let’s go. Let’s put on some Aretha, let’s listen to Ray Charles’s “America the Beautiful,” let’s fight some Illinois Nazis, and let’s save America. It is, after all, a mission from God.

Leave a Reply