A Race & Ethnicity Approach to Clash by Night (1952)

Clash by Night (1952) – Race & Ethnicity

Last week, my husband and I had a date night at The Brattle, one of our favorite things to do and as we did on Valentine’s Day to see Casablanca (1942). Incidentally, that Casablanca review is one of my favorites that I’ve written because it explores both his and my readings of the film and how our interpretations evolved in discussion with each other. Bringing people together to interrogate art as an expression of the self – that’s the beauty of cinema! And so we did again with last week’s viewing of Fritz Lang’s Clash by Night (1942) as part of The Brattle’s Noirvember series of film noir classics.

The Review Roulette wheel landed on Race & Ethnicity as our approach this week, and I think it’s actually a fascinating one for such a discussion, but I’m also going to pull in another film for the purposes of comparison: A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) which I have also reviewed. (Both reviews of Casablanca and Streetcar have been added to Black & White & Read All Over).

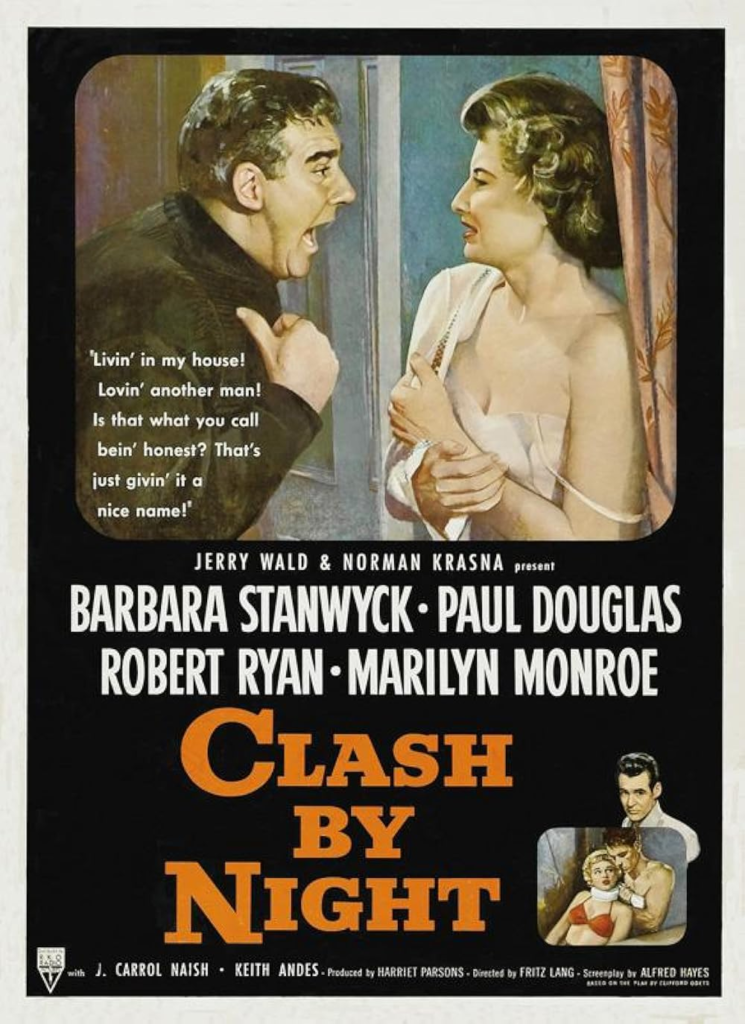

So, Clash by Night is about a wayward woman, Mae (Barbara Stanwyck), who returns home to the small fishing town where she grew up after a decade away. We gather that she had an explosive and proud departure, as her brother is less than enthused to see her, though his girlfriend Peggy (Marilyn Monroe) is very eager to meet this legend. Mae is aggressively independent, even misguidedly so, and is in desperate need of learning the lesson that relying on other people, trusting their love, is good, actually. I won’t lie, I resonated with Mae far more than I like to admit, which, too, is the beauty of cinema!

So, Mae is a wild spirit who has been wounded – she “fell in love” with a married politician who suddenly died and left her with money his wife disputed and won. She returned home bitter and angry at men, longing for the life she promised herself without the means to provide it or the reality to support it. Her want for something more is rooted in a false sense of entitlement and an all-too-real sense of disappointment in having attempted a shortcut to love, security, and success that left her a heartbroken, vulnerable failure.

While sulking at home, Mae is courted by a lovely, simple, gentle giant of a man, Jerry D’Amato (Paul Douglas), who introduces her to his friend Earl Pfeiffer (Robert Ryan) who is his exact opposite. Earl is god awful. He’s sexist, racist, violent, angry at his wife for traveling the country as a vaudeville performer, bitter about being left behind, and confident. He’s confident that he’s the smartest person alive who’s truly figured it all out and everyone else is a sucker for getting fooled into going along with the system. God he fucking sucks. He does a horribly racist impersonation of Chinese stereotypes that goes on for way too long while simple Jerry laughs and Mae looks on in disgust. He’s crude and rude and a MESSY bitch, so, naturally, all the worst parts of Mae believe that she doesn’t deserve any better.

Mae and Jerry marry and have a baby girl together, and throughout her first year of motherhood, Mae begins to spiral. She becomes bored with Jerry being the perfect supportive husband, and she becomes restless in the security of her life, longing for the forbidden romance she had with her politician who made her feel confident and sexy and wanted. And she gives in to the tornado that wants to stir the pot and rock the firm foundation of her relationship with Jerry just to prove to herself that it can break if she pushes hard enough and that she doesn’t deserve the love, security, and success he offers her. So she pushes, has an affair with the absolute slop she thinks she deserves, and lives to regret it.

So where does Streetcar come in? I think these two films are a fascinating pairing for depictions of ethnic stereotypes. In Streetcar, Stanley Kowalski is a brute, very much like Earl in mannerisms but with the brawn of Jerry. He’s filled with unearned confidence and pontificates on things he believes are simple only because he misunderstands them. His arrogance and brutishness is explained in the film as a byproduct of his Polish heritage. Likewise, Earl’s last name indicates Germanic heritage. These stereotypes could potentially be hangers on of post-WWII attitudes towards these communities in the US or they could just be reflective of the source texts and authors’ own views, but what is significant here is the type of masculinity they are portraying.

Both Stanley and Earl are extremely toxic individuals who echo one another in their violent determinism not to let others see them as human. Their views of masculinity displace them from the humanity of the people around them, especially when they are not in manipulative control of the women they associate with. This depiction is clearly a negative stereotype of central European men, and it’s striking how monotone these two characters are. Even in scenes where you want to sympathize with the character – for instance, when Earl drinks himself into a stupor after his divorce – their depiction thus far has made sympathy nearly impossible. It is not a kind portrayal but one heavily influenced by the worst stereotypes of men from these backgrounds.

Both of these are in stark contrast to Jerry and his immigrant father, Papa D’Amato (Silvio Minciotti). Jerry seems to be an Italian American who grew up with Mae in this California fishing town while Papa seems to be from Italy directly, as he is the only person we meet in town who speaks very broken English. Both Jerry and Papa are portrayed much more favorably with positive Italian stereotypes of good hospitality, strong work ethics, and a romantic idea of love and family. For instance, Papa in particular hates Earl whom he sees as a lazy, aggressive brute because of both his hatred of working and the way he treats Jerry and, eventually, Mae. Jerry is the polar opposite of the masculinity Earl and Stanley represent. His gentleness and trusting hospitality often lead to him being guided by that worse type of masculinity such as when he laughs at Earl’s racist imitations, but he also comes to learn why Earl is such an awful influence on him and his wife. He grows from that trusting place to a more cautious and thoughtful man, particularly after Earl pushes him to violence. However, unlike Earl and Stanley, the moment Jerry places his large hands on Earl, he is disgusted with himself, livid at the thought that he almost hurt someone.

These portrayals of different types of masculinity as mapped onto ethnic stereotypes in the post-war period are interesting cultural shorthands to include. Papa’s presence and limited words in English are pointed reminders for the audience of the diversity not only of characters we meet but also the American community in the town. Where Jerry embraces everyone in town with openness until proven otherwise, Earl fights against everyone, needling to find the worst in people so as to exploit it by dragging them into his own miserable outlook on life.

Ultimately, this film is a battle between these types of masculinity that are represented by the positive and negative stereotypes of different ethnic communities. Clash by Night argues fervently for the gentle kindness of Jerry to pull Mae from the maelstrom of misery Earl brings to her life, crashing like waves into her already rocky demeanor. Jerry’s soft Italian stereotypes and gentle masculinity offer her space to be flawed and human while also loved, secure, and supported, attributes she desperately needs in a partner.

Leave a Reply