An Apparatus Approach to A Streetcar Named Desire (1951)

[Content Warning: Discussion of sexual assault, statutory assault, domestic violence, PTSD, and suicide]

A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) – Apparatus

If you are reading this as it posts, I am in New Orleans eating a steamboat’s worth of beignets and openly recreating that scene from When Harry Met Sally with each bite.

In anticipation of my travels, this week I watched Elia Kazan’s A Streetcar Named Desire (1951) for the first time since I was a teen who absolutely did not pick up on a lot of the complicated nuances in either the Tennessee Williams play or its film adaptation. The Review Roulette wheel landed on Apparatus for our approach, so let’s dive into those complexities a younger me simply did not appreciate enough, let alone recognize at all. This review will deal with very heavy topics, so please heed the content warning above.

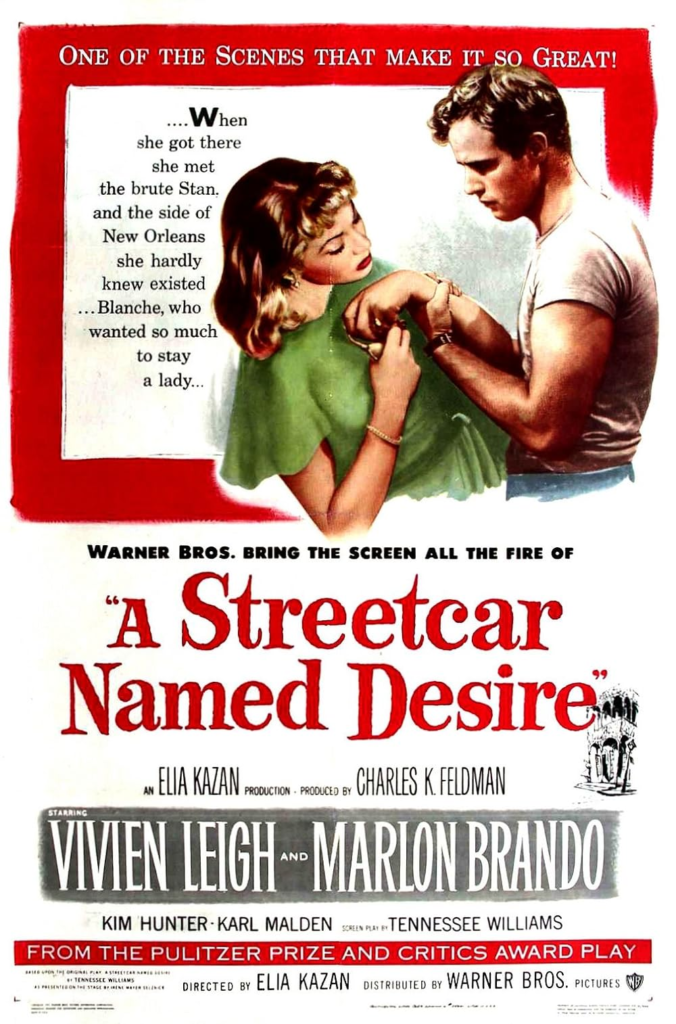

You might already be familiar with the beats of Streetcar just by virtue of living in society if you have not read or seen an adaptation of the play. The story follows Blanche DuBois (Vivien Leigh), a quintessential Southern belle who moves in with her sister and brother-in-law, Stella and Stanley Kowalski (Kim Hunter and Marlon Brando), in New Orleans. Blanche has left her ancestral home, Belle Reve, in Laurel, Mississippi and suggests to Stella that she is on leave from her job as an English teacher due to her nerves, but as we learn, Blanche has been living in a hotel, having lost Belle Reve to financial difficulties, and was dismissed from her position due to impropriety with a student. As her seemingly brief stay turns into five months, Stella’s brute of a husband, Stanley, becomes even more blatantly and physically abusive until he eventually rapes Blanche, whose mental health then completely shatters, resulting in her being institutionalized.

The story requires the audience to embrace nuance; you cannot view this film with any semblance of good vs. bad dichotomization or healthy vs. toxic or right vs. wrong. I believe that for all art, but for what I want to say about this film, I need to be clear that I am not discounting any opinions or interpretations that I don’t specifically name, and I am not excusing anything or saying better/worse/equal when I compare situations, crimes, and circumstances.

As a reminder, the Apparatus approach requires us to think about the ideological structures of society within the film and the ways in which they are portrayed. There are many ways you could analyze societal structures in Streetcar which I’m sure have been written to death such as thinking about the place of dubious prominence the DuBois family may have had in their centuries-old Mississippi plantation; or, reading into Stanley’s insufferable, archaic insistence on bringing up the Napoleonic Code that a woman’s property is also her husband’s; or, the tragedy of Blanche’s late husband, a man she married when they were both very young and who died by suicide after she presumably discovered and berated him for his homosexuality. I want to focus on a different sensitive topic: Stella’s entrapment between two abusive individuals under the influence of the patriarchy and societal expectations of family.

Repeatedly throughout the film, Blanche refers to the dingy apartment Stella and Stanley share as a trap. She says that she wants to take her sister from this place and free her from the clutches of Stanley who is likewise repeatedly referred to as a variety of animals. This image of their marital home as a barred cage in which Stella and, subsequently, Blanche are trapped with a predator is evocative and not incorrect as is ultimately realized when Stanley physically assaults Blanche.

Stanley is abusive. This is not really in question at all in the film. Stanley and Stella’s marriage is paralleled with the older couple upstairs who are constantly fighting and hitting each other and who take in Stella every time she and Stanley have a row before Brando screams his iconic “STELLAAAAAAAAAAA” and she returns, seductively and silently asserting her assumed sense of power in their relationship as she slinks down the stairs back to their abode. In this sense, the apartment is not a simple trap but rather a complex system of traps that portrays very well the tangled web abusers can weave, the false sense of superiority and control they can offer their victims, and the enabling behaviors of outsiders encouraging them to walk back through the door to spring the trap once more. Blanche is right to want more for Stella for both her safety and that of her imminent baby. What Blanche deflects, however, with her insistence that Stella’s home is a trap is that she does not want to free her sister; she wants to take over her confinement.

Blanche has PTSD. She married very young when she was head over heels for a sensitive boy. He wrote poetry and love letters, and the 16-year-old Blanche DuBois, in all her sensational, old-fashioned naiveté, was smitten. When she discovered his sexuality in an undisclosed way, she admits that she told him he was weak, believing that her words were the catalyst for his death. This horrible tragedy understandably left Blanche mentally suspended in a youthful state of guilt, physically aging into her 40s, and emotionally volatile to those around her.

Seeking help for her PTSD is not presented as an easy option as the only mental health intervention we see is full incarceration at the end. Stella actively resists engaging with the harder topics her sister tries to talk with her about, even saying that in order to continue living with him, she cannot allow herself to accept that Stanley may have raped Blanche. Blanche receives no mental health support in this film, and I am by no means blaming her for her emotional volatility in a world in which seeking help was so difficult and even openly discouraged.

Blanche recounts several times the number of deaths she has witnessed at Belle Reve since Stella left and presumably after witnessing the tragic death of her husband. Every family member they had, immediate and extended, has died and been buried at Belle Reve under Blanche’s watch. She has experienced grief and loneliness and abandonment as she lost her husband, her ancestral home (the name of which translates to “beautiful dream”), and her sister to a man who abuses them both. In all of this loss, she developed an obsession with vitality and youth and deception to create a fictional world in which her fictional self could be a proper Southern belle in her plantation home with beaus and suitors and pretty dresses. When her fictional, idealized world clashes with her reality in which there is no support for her mentally and no one who understands her trauma to help her navigate society, she becomes volatile.

Blanche’s obsession with youth is multi-layered and present in every scene of the film, but there are two moments when the depth of the obsession becomes very clear. A teenage newspaper boy comes to the apartment when Blanche is home alone, and she forces herself on him, kissing the stunned boy who leaves abruptly after. Later, Stanley reveals that Blanche lost her job because she pursued a sexual relationship with a 17-year-old student. Blanche contextualizes this statutory rape by fitting him into the larger picture of her recent decades in which she turned to a stream of strangers to provide human connections, intimacy, and short-lived romances so that she would not form attachments from which to be abandoned while looking for emotional support to get through her traumatic daily life.

Streetcar is an intense film, a phenomenally acted, timeless film, in my opinion. And I think it’s really important to analyze the harshest realities within it. Stanley is a man who repeatedly talks about his place in society, in his household, and in his marriage as a king. He demands respect because that should automatically be afforded him in society. He rapes Blanche to exert power over her after he feels she has disrespected him, empowered his wife to speak back to him, and taken over his domain in his own home. Stanley benefits from a patriarchal society, working and living in social circles that encourage his behavior as manly and primal, and because of this, he knows he will have no consequences for raping his mentally unwell sister-in-law.

Blanche, on the other hand, commits a similar crime on paper, and is derided, gossiped about, made homeless, abused further, stripped of the possibility of redemption, and ultimately incarcerated in an asylum, largely because there was no intervention when her mental faculties started to deteriorate. Her actions are not excusable. The context of how society failed her, however, helps to explain them and, in turn, offers an intriguing foil to a man she echoes. Stanley and Blanche both have stunted emotional, mental, and intellectual growth. Both act as teenagers: Stanley because society also failed him, never demanding more of him and allowing him to plateau at the peak of his aggressive immaturity; Blanche because she experienced a traumatic event at a young age that fractured her mental state into a guilt-riddled half and a placating balm when the former gets too much, obsessed with costume jewelry, Southern refinement, and young boys.

Stella is stuck between the two of them. While she refuses to engage with the worst of the demons plaguing her sister, Stella does try to open her home to Blanche and care for her in a way. Her refusal to have ever returned to Belle Reve, her reluctance to allow Blanche to suck her back into her former stuck-up, assertive Southern belle self, and her resolve to lead her own life and stand up to her sister do all point to the idea that Stella left home for a reason: to free herself from the trap of societal expectations of her family in search of a different life. Unfortunately for Stella, she only moved her incarceration to Stanley’s home in New Orleans.

In the final moments of the film, after Blanche is taken into custody by the asylum caretaker, Stella takes her baby up to her neighbors’, vowing to never return to Stanley. We could read this as Stella falling into the same complex trap in which she will saunter back down, baby in hand, returning to her normal life with her abusive husband. Or we could read more optimism into it. Stella knew that to some extent her sister and husband were both challenging individuals, but after learning of the extent of both of their sexual crimes, I would like to believe that Stella is ready and strong enough – while holding her baby and having sent her sister for institutional help – to recognize patterns of abuse, both in terms of the patriarchy (Stanley’s precious Napoleonic Code) and generational (the societal expectations represented in Blanche of Southern belle etiquette, ancestral homes, and familial obligations). I want to believe that Stella now understands the stakes of not only returning herself to Stanley’s trap, but also bringing her baby boy along with to learn with that type of man as a father.

Nobody is perfect in this film, and that is clearly the point. Stella could have done more to help her sister, but she is not at fault for not having done so and is herself struggling with societal pressures, interpersonal manipulations, and internal denial about her own role in her relationships. And I think this is the important part. Streetcar presents us with an exaggerated example of an everyday situation (a sister-in-law stays for an extended visit) and caricatures of individuals in that situation (the worst guy you will ever meet, a severely traumatized woman, and the middle ground between the two), and asks us to relate it to our own lives. I think that simplicity of concept with the extremity of its execution is what makes it such a timeless cultural work. Not many of us would be Stanley and hopefully fewer of us would be Blanche with all her trauma, but any of us could be Stella (or a significantly pared down version of the other two). And I like to think that Stella is going to try to find a way to break through societal structures, like patriarchy and familial expectations, to forge a better life for her and her son, learning from the ways those structures failed her sister and husband so horribly. Maybe Stella is the star to strive for and all we can really hope to be in such a complicated, painful world; imperfect, but trying.

Leave a Reply