A Marxist Approach to Gods and Monsters (1998)

[Contains spoilers]

[Content warning: suicide, sexual harassment and assault]

Gods and Monsters (1998) – Marxist

Technology is gonna get your ass every once in a while. I guess that’s a real through line to Frankenstein in a way. We put faith in these creations of man with the hubristic idea that we can control them. Mary Shelley of course knew we couldn’t and that the hubris of creating the technology in itself was the true abomination of man, not the horrors wrought by the being that became of them. The creator is always the villain, the monster merely a tortured result of the villain’s cruelty. (I tried to fix my laptop and it’s now with Geek Squad for the weekend because I janked it up so hard. This week’s review will be shorter and typed on my phone, hubristically.)

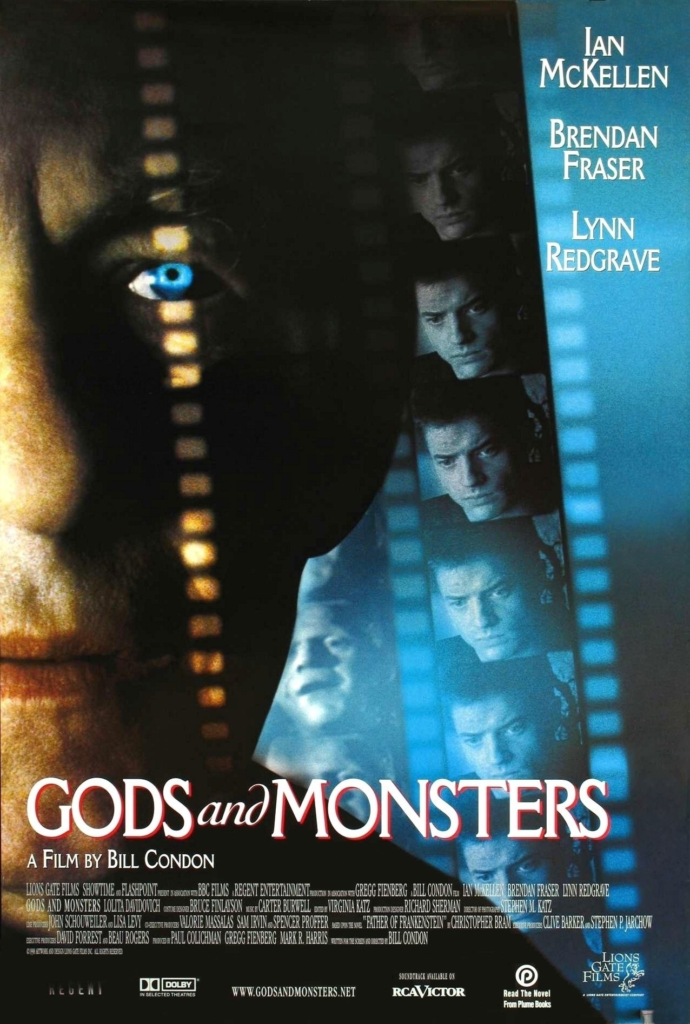

So, to continue our Spooky Season Monster Mash, this week I wanted to look at a gorgeous little film about the end of James Whale’s life. Whale directed last week’s film Frankenstein (1931) as well as Bride of Frankenstein (1935) and a host of other films in his short directorial career 1930-1941. He was also a veteran of WWI, openly gay, and utterly human. His work expresses sorrow, joy, humor, loneliness, rage, torment, and the beautiful horrors of consciousness. All of this is captured in Bill Condon’s 1998 film Gods and Monsters (adapted from the novel Father of Frankenstein) starring Ian McKellen as Whale and Brendan Fraser as Clay Boone, Whale’s gardener.

There are many very beautiful things about this film, but the Review Roulette wheel landed on Marxist for our approach this week, so I want to focus on class dynamics in the film. We could easily have had a discussion from Queer and Disability perspectives on the leads, or Feminist with Whale’s housekeeper and carer Hanna (Lynn Redgrave) or the long life of the character of the Bride of Frankenstein and her maternal influence on both Whale and this film. This movie is incredibly rich for analysis with intriguing lines to dig into, acting choices that evoke scores of interpretations, and scene blocking that blends a surrealist filter onto some shots in a way that brings Whale’s pioneering horror films to the fore. But, for a Marxist critique, we’re going to look at how the worker is literally posed in this film.

The first thing to say is that McKellen is exceptional. In all things, really, but particularly here. I’m going to spoil this film because analyzing it how I want to requires knowing the ending, but I do hope you will still watch it or stop reading this review here so you can watch it first and then come back.

Gods and Monsters is about Whale getting close to a hunky Brendan Fraser in 1957, a time when homophobia was especially potentially deadly. We see both initially as negative stereotypes: a catty, wealthy, prowling older gay man and a simple, brawn over brains, brutish landscaper. Naturally and carefully, these two ends of a spectrum come closer together, cross, and end somewhere closer to the opposite’s stereotype.

Last week, I introduced this concept of cultural crystals in talking about Whale’s Frankenstein, and I want to come back to that. Gods and Monsters is very much an adaptation of Whale’s film but with speckles of the original Shelley novel while pulling reality into it with real beats of Whale’s life, particularly his death. In both the film and in life, Whale was suffering terribly from a series of strokes, depression, and deteriorating mental faculties. Here’s the spoiler: in the film, Whale is not pursuing Fraser sexually as set up, but rather as a way out.

Fraser’s character, Clay Boone, is very aptly named: a blessing of clay. A fresh, malleable, earthly man answering Whale’s prayers for an end to his miserable suffering. As soon as Whale sees the man, he begins to imagine molding him into his second monster, the perfect cinematic finale to a filmmaker’s life. Death in homage of a career’s overture that overshadowed everything that came after. Unfortunately for Whale, Clay is unwilling to be made into a monster.

Clay is a laborer who is desperate for money both to support himself and seemingly to send home to his siblings who live at home in the Midwest. Despite his misgivings and stereotypical homophobia, Clay agrees to sit as a live model for Whale to draw, as Whale needles him with increasingly graphic stories of sexual partners, party-goers, and nude models, trying to provoke a violently homophobic attack from the brute. While Clay does react explosively, he comes back to apologize and sit again not only for the money but also the need for a human connection that has been awakened in him. In Whale’s attempt to create a violent monster, he instead, accidentally, gave life to a long silenced soul.

Whale can’t see past the stereotype of a man of Clay’s social class, a landscaper who lifts heavy machinery and is seemingly a former Marine. He sees an unthinking brute in need of money who has killed before, however nobly in war, and might again for mercy. Clay, though, never went to war. He carries a lighter with the Marine insignia despite not having finished bootcamp. He has the heart and mind of a pacifist trapped in the body of a brute, the very essence of Shelley’s monster. I note the mind because it marks a clear distinction from Whale’s monster whose brain is pointedly taken from a criminal. Whale’s monster is still only murderous in self-defense (and guilty of accidental manslaughter in a playful tragedy), but the specificity in the phrenological suggestion that the brain is from a criminal is echoed in Whale’s projection on Clay’s stereotype in Gods and Monsters.

Clay is very clearly labeled as a poor, simple man from his first scene, while Whale’s own impoverished childhood is only revealed in bits throughout the film. He has long been running from his past as a factory worker in his teens with a family who misunderstood him and the years he spent in WWI that left trenches of trauma in a mind now not strong enough to keep them at bay. He afforded himself the qualities of complexity and depth but refused them to Clay, in turn refusing Clay his humanity as a way to justify buying him and encouraging him to be monstrous.

Ultimately, Clay’s unforeseen complexities are really no more remarkable than anyone else’s. He is a simple man, but the simple truth is that all men are complicated creatures. Even Whale’s monstrous act is complicated. He is an old man whose real overture – an early life of trauma, loss, and horrors – is reprised at the close as his mind deteriorates into incessant memories of pain. He wants to end this suffering, but in his attempt to do so, he transfers some of that trauma, horror, and pain to an innocent person, actively trying to ruin someone else’s life by triggering a murderous impulse unnatural to him.

In a perfect twist, Clay, ultimately, is not Whale’s monster, not even Shelley’s monster; Whale is. His monstrous act is the result of humanity’s evils, societal wrongs against him. Men who thought they could be Gods wielding weapons and chemicals and hatred against men from lower social classes, bestowing death and trauma on people they didn’t see as equals; men who deigned themselves leaders, who used technology that revolutionized the concept of warfare while, in practice, decimating humanity with every canister blown and magazine emptied; men who proved the pursuit of Godliness was the truest route to monstrosity, created Whale. And, for many years until his illnesses overtook him, Whale processed that trauma into art with a beautiful gift for communicating the complexities of human emotions through comedic horror cinema that established a cultural crystal of influences for almost a century now.

Aren’t humans amazing? What a stunning, complicated film in the Frankenstein life cycle. Next week, Monster Mash will get away from Frankenstein lore, but I can’t promise the week after will. You’ll have to walk this way to find out.

Leave a Reply