A (Kinda) Genre Approach to The Wizard of Oz (1939)

The Wizard of Oz (1939) – A (Kinda) Genre Approach

It’s the most wonderful time of year when days cease to exist and we can plunge into the realm of reality where we should always reside: watching movies and eating leftovers to our hearts’ content. (That is unless you have a job far more crucial to society than my unemployed ass, in which case I appreciate you and the work you do!)

On Christmas Eve, my husband and I saw Wicked (2024) (which I found supremely entertaining), so this week, I thought it would be interesting to think about the classic 1939 adaptation of the L. Frank Baum book The Wizard of Oz. And then halfway through watching it, I had a horrible, terrible realization that we of course now have to talk about:

The Wizard of Oz is a Christmas film.

BEFORE YOU COME FOR ME, hear me out. The Review Roulette wheel landed on Marxist for our lens, but I’m sorry, we have to do this. We have to come to terms with this fact, but we can do so together, as friends. So this week, for our final Christmassy review (i.e. low-key and casual), let’s put down the pitchforks and take a Genre approach to The Wizard of Oz. HOWEVER, I will put the caveat that this is about the production and distribution contexts of the genre. Stick with me.

(I have had an influx of new subscribers recently (Welcome!), so if you are new here, I have a PhD in Christmas film history (and also government subversion, Hollywood history, and post-war/early Cold War cultural production), so this is a normal thing to talk about, I promise. (I also use a lot of parentheses.))

If I wanted to be a tool, I could argue that the Wizard (Frank Morgan) is a satirical Santa Claus who does indeed possess magic in that Santa-esque way, but his primary function is to reinforce moral growth in children. The ultimate revelation of the Tin Man’s heart or the Cowardly Lion’s courage is that they had it all along, prompted to tap into those inner-strengths by committing a cheeky murder with friends and realizing their true potential along the way with prompting by the Santa figure. But I’m not going to make that argument because even I think it’s a stretch. Instead, we’re going to think about the far more interesting (in my opinion) legacies of The Wizard of Oz, specifically with regard to two other Christmas films (out of chronological order for a reason): Disney’s 1961 Babes in Toyland and, of course, Frank Capra’s 1946 It’s a Wonderful Life.

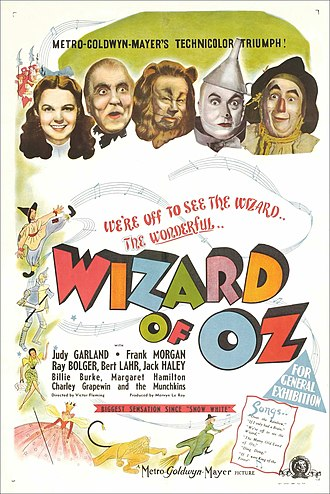

With regard to Babes, what I find most interesting is the very long history between Disney and Baum’s work. Some juicy context: After Disney’s overwhelming success of adapting a children’s story to film in Snow White and the Seven Dwarves (1937), MGM acquired the rights for Baum’s 1900 book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. With director Victor Fleming and actors including Judy Garland (Dorothy), Ray Bolger (Scarecrow), Bert Lahr (Lion), and Morgan as the Wizard and other key roles, the 1939 film adaptation was a critical success (but financial flop until subsequent releases in the 40s).

Disney wanted in on some of that Ozian magic but was having its own financial issues, lateral growth, and brand development to deal with throughout the 40s and 50s (let alone the WWII, post-war, Cold War contexts it was working within). By 1961, though, Disneyland is open, they have books and comics and toys and television shows and the rumblings of ideas around “intellectual property” and lawyers and Walt Disney himself has proved to be a genius at cultural capitalism the likes of which we might not have seen until Taylor Swift. So, what does Disney do? Make a “Christmas” film that really has fuck all to do with Christmas except it’s about toys and they vaguely mention the need to make the toys by December so Santa can deliver them. What Babes in Toyland is instead is a feature-length advertisement for Disneyland that loosely follows the beats of The Wizard of Oz with similar themes.

In both films, we have a female protagonist who has the object of her affection threatened by the villain. In order to get back to her family once reunited, the two go on a journey through a forest with talking, threatening trees, and end up in a fantastical place with an eccentric older man who ultimately helps the protagonists realize their potential with some cheeky murder.

They are not one-to-one and I’m not claiming they are. They are, though, tapping into similar things and I do think that Disney was thinking about Dorothy’s 1939 adventures in Oz because he was definitely thinking about Snow White’s 1937 ones. The audience in 1961 were primarily baby boomers (1946-1964) and their parents who were most likely children to teens in 1937 when they would have seen Snow White in cinemas. The Wizard of Oz and Babes in Toyland both build these mystical, magical lands that feel so otherworldly and colorful and new to children and develop a sense of escapism during periods of national turmoil (Great Depression and Cold War, respectively). They have these comical, over-the-top charlatans with hearts of gold in the Wizard and Ed Wynn’s Toymaker, and it’s no coincidence that Wynn was slated for the Wizard in 1939 but declined it. Ray Bolger is even hamming it up with physical comedy and dance numbers in both, though in very different characters as the Scarecrow and the villainous Barnaby. There’s a kinship in the spirit of each of the films, and, no, I don’t think that that alone is enough to call The Wizard of Oz a Christmas film (we can barely call Babes one), but it was enough for some television stations to, which brings us to my boy Frankie Caps.

It’s a Wonderful Life wasn’t a huge success either until subsequent releases, namely on television. In 1974, the copyright lapsed on the film, and television stations could show it as much as they wanted for nominal royalty fees, and boy oh boy did they until It’s a Wonderful Life became a staple of the American Christmas holiday from then on. Copyright changed eventually but the film is still shown annually in the US and has become beloved over time, very much like The Wizard of Oz. The Wizard of Oz, similarly, has had annual showings and Christmas specials tied to its presentation at key points in the last 75 years, being shown primarily between November and December since the 1990s especially. Both are phenomenal cinematic masterpieces (in my opinion) and earned their places as timeless, relatable films over many decades as fixtures in American lives, embedding themselves further in the cultural identity of 20th century America with every subsequent release and broadcast in the rapidly changing modern world.

Some people also argue that Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life isn’t a Christmas film. I don’t agree with them, but I get what they mean, and it is all part of the Die Hard debate that just won’t die: what makes a Christmas film? As I have said here and elsewhere many countless times, a Christmas film is a film you watch at Christmas. It’s not sexy or bold or argumentative, it just is what it is in a sweet recognition that we don’t have to police joy and peace.

We all have traditions. Christmas traditions may be shared across countries, states, regions, communities, or just within your own household, and they may look like how others celebrate or they might be totally different. You might celebrate Christmas in mass or in Macy’s or in both or not at all; you might have 40 people over for the Feast of Seven Fishes on Christmas Eve, or you might have a Christmas/Hanukkah hybrid at a Chinese restaurant as my husband and I did this year. You might settle in for your annual re-watch of White Christmas or Home Alone or every James Bond film ever made or The Wizard of Oz, just because it brings you peace and taps into that annual escape into a well-constructed nostalgic framework of security in a place where clouds are far behind and trouble melts like lemon drops. And every single one is valid.

Whether you celebrated Christmas, are celebrating Hanukkah or Kwanzaa, or are observing any other religious or secular traditions this season or none at all, I hope it’s a wonderful time of the year for you that brings you peace and joy and all the leftovers you could possibly scarf down while watching a comfort film.

Leave a Reply