A Disciplinary Approach to Miracle on 34th Street (1994)

Miracle on 34th Street (1994) – Disciplinary

Happy December, darlings!!!

If this is your first holiday season with Review Roulette, welcome to the least formal portion of the newsletter in which I write rapidly because, like Santa, December is my busiest month of the year by far. Being a Christmas film scholar ain’t for the faint of heart, but it is for the full of heart. You gotta really, really love Christmas because you have to defend yourself constantly, and there’s never not a moment when your mind is Christmas song-free. If you are curious about my book (shameless plugs incoming here, throughout, and at the end), Selling Out Santa: Hollywood Christmas Films in the Age of McCarthy, please do check it out!*

So, please, hang them stockings, deck those halls, and unwrap a little gift for yourself by indulging in a little Chaotic Christmas with me all month long.

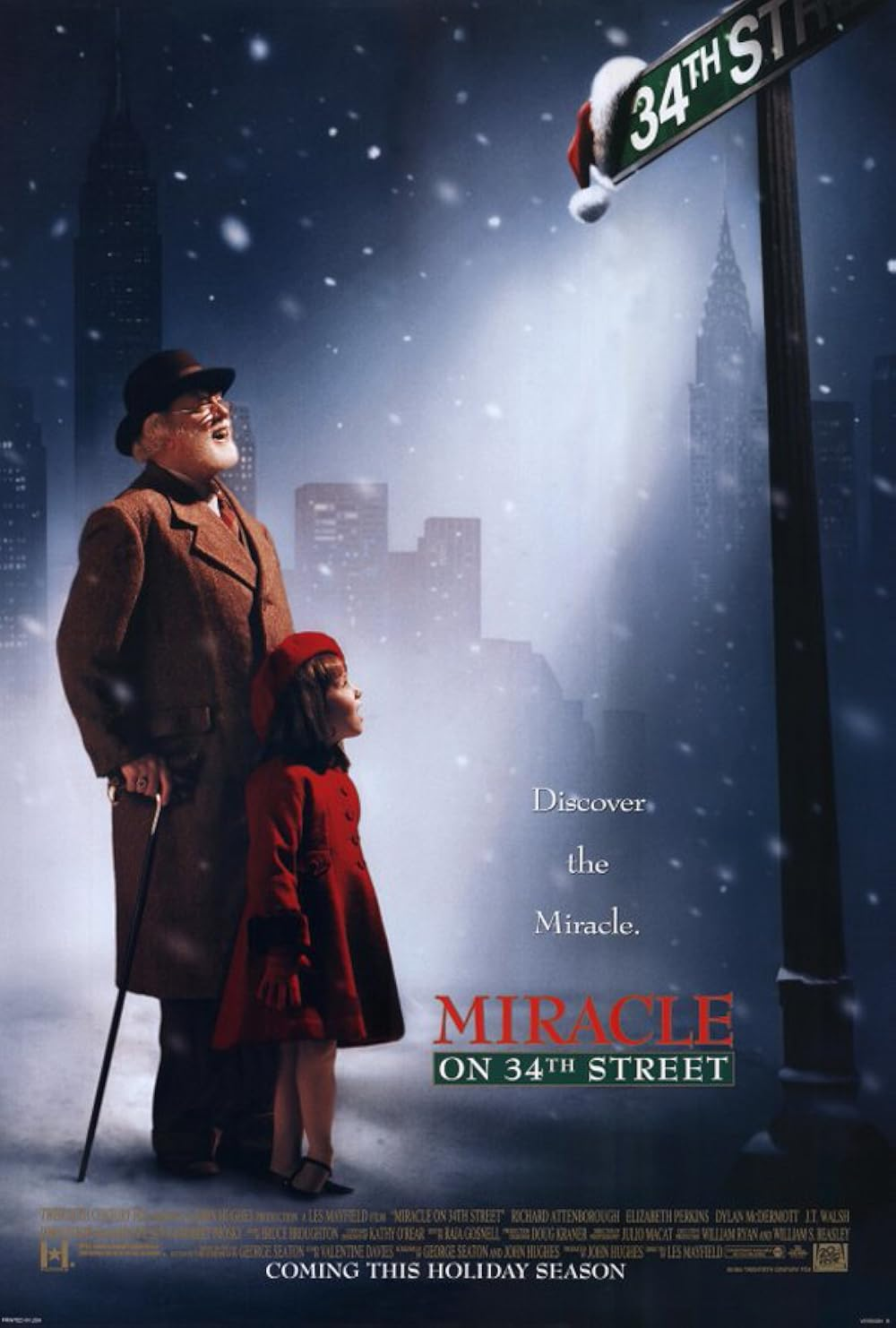

This week we’re talking about Miracle on 34th Street (1994) and, no word of a lie, the Review Roulette wheel landed on Disciplinary as our approach. I’m sorry, but I gotta do it to ‘em.

My discipline right now just so happens to be Christmas film history, as said many times here and everywhere (vague plug 2), so how does this version fit into Christmas film history broadly? First things first, it is absolutely essential for us to know and scream from the snow-covered rooftops that Christmas is as diverse as the American people and their history, meaning that Christmas is for everyone. It is sometimes religious, but it’s mostly secular in American history. The vast majority of the time, Christmas is secular in American history. Rooftops. Scream it.

Except for in this version of Miracle. Kind of. But even then it’s just in a vague conversation with religion. The Christmas parts of the film are still largely not engaging with any nativity-esque ideology; rather, the only real links we can make are that Christmas spirit values are similar to proclaimed Christian values and both require faith.

So, I’ve written a ton about the 1947 original Miracle such as in this Open Access article and in my book (plug 3), but I’ve only seen the 1994 one twice: once in childhood and once this week. The films are roughly similar. The 1994 one is very clearly updated for the 1990s in that the villain is not the store psychologist as in the 1947 version, but instead the bad guys are a rival store. Specifically, a discount store called Shopper’s Express which gives us a fascinating commentary on where commercialism is in the 90s as opposed to the 40s.

In that article and my book (so sorry, 4), I talk about the significance of department stores in American history as places that defined communities and supported urban centers financially. They became these hubs of communal services in cities and, on that trajectory as they grew in popularity and purpose from the late 19th into the early 20th centuries, Christmas displays, extravagant windows, and store Santa Clauses grew too. However, post the post-war, this changes significantly. In the 50s there’s an explosion of suburbia that changes how and where people shopped, by the 80s we have a huge prominence of shopping malls with department stores serving as anchor stores, and by the 90s, there’s a mainstreaming of bargain stores operating as vague lesser ghosts of department stores.

So, this 1994 version makes the whole idea of a department store Santa even more deeply nostalgic and a symbol of a specific type of commercialism that the film argues has more value, soul, and character than the vaguely named Shopper’s Express. For this Santa, shopping is still a special part of the American Christmas ritual, but for Shopper’s Express it’s just something to do quickly and efficiently.

So, it’s almost close to the original: there’s a drunk Santa on the Thanksgiving Day parade float, our Santa (Richard Attenborough) berates him, Elizabeth Perkins hires him for Cole’s department store (not Macy’s in the 90s), he does the goodwill policy, Alison Janney is very aggressively in support of a Santa that would send her to another store for a deal, yadda yadda yadda, Shopper’s Express has drunk Santa allege Richard Attenborough Santa is a pedophile (not in the original), Richard Attenborough Santa hits him with a cane, Shopper’s Express goons get him arrested, and Dylan McDermott Lawyer defends him in court arguing that Santa can’t be put in a mental institution (same as original).

Side bar: Dylan McDermott is also Elizabeth Perkins’s neighbor and he’s obsessed with her and her daughter Mara Wilson, and they go on ONE DATE and at the end of their FIRST DATE, Dylan McDermott hands Elizabeth Perkins an ENGAGEMENT RING. What kind of psycho buys an engagement ring before their FIRST DATE? And then, AND THEN, spoiler, they get fucking MARRIED. She says no to the engagement and then Santa tricks them both into going to a cathedral after midnight mass on Christmas Eve and they just get married. It’s absolutely fucking bonkers.

So, anyway, Santa’s on trial for being kooky and violent, and the judge is trying to get out of it because he’s sad about having to send Santa to Bellevue. In the original, there’s a more interesting direct incentive in that the judge is up for re-election and his campaign manager is like “you need voters to retain your seat, and you know what voters have? Children who believe in Santa Claus,” which is one of my favorite places to inject political strategizing in any film.

So, here’s where it’s different from the 47 version. In 47, the judge is looking for a way out and the US Postal Service delivers a bunch of “Letters to Santa Claus” to the Kris Kringle in the courtroom, therefore establishing that the US government officially recognized him as Santa and ending the trial with the judge taking a cop out. In 94, during his closing remarks in court, Mara Wilson hands the judge a Christmas card with a dollar in it with the words “In God We Trust” circled, therefore establishing that the US government does not require proof to acknowledge and endorse the existence of God, and so New York has precedent not to require proof to acknowledge and endorse the existence of Santa.

Which is a crazy fucking change.

Those are not the same thing. Those are huge differences in the movies that kind of look the same. But the interesting part is that “In God We Trust” was added to paper money in 1954, so even if they wanted to go in that direction a few years before, it would’ve had to have been a bunch of loose change in a card, and you can’t really circle words on a coin, so the meaning probably would have been lost on the judge. Anyway, we added those words to the paper money to show the world we weren’t godless Commies.

And that’s why Hollywood Christmas Films in the Age of McCarthy (and beyond) are so damn interesting (5, wowza).

This movie is a hardcore 90s Christmas film through and through. This Christmas, I hope you enjoy whichever you prefer! Or neither, you do you, boo.

*Selling Out Santa: Hollywood Christmas Films in the Age of McCarthy is Open Access from the publisher and the ebook download is free from Barnes & Noble, but I would ask that if you like what you read, please consider buying a copy for yourself and/or a friend because I am unemployed and by the time royalties pay in July 2026, I will have been unemployed for over 2 years. I’m sorry to ask, but if you can swing it, please do or if you enjoy the book and you’d like to leave me a little holiday present that’s not the full price, please consider a little Venmo gift this Christmas (@Vaughn-Joy). Thank you, darlings!

Leave a Reply