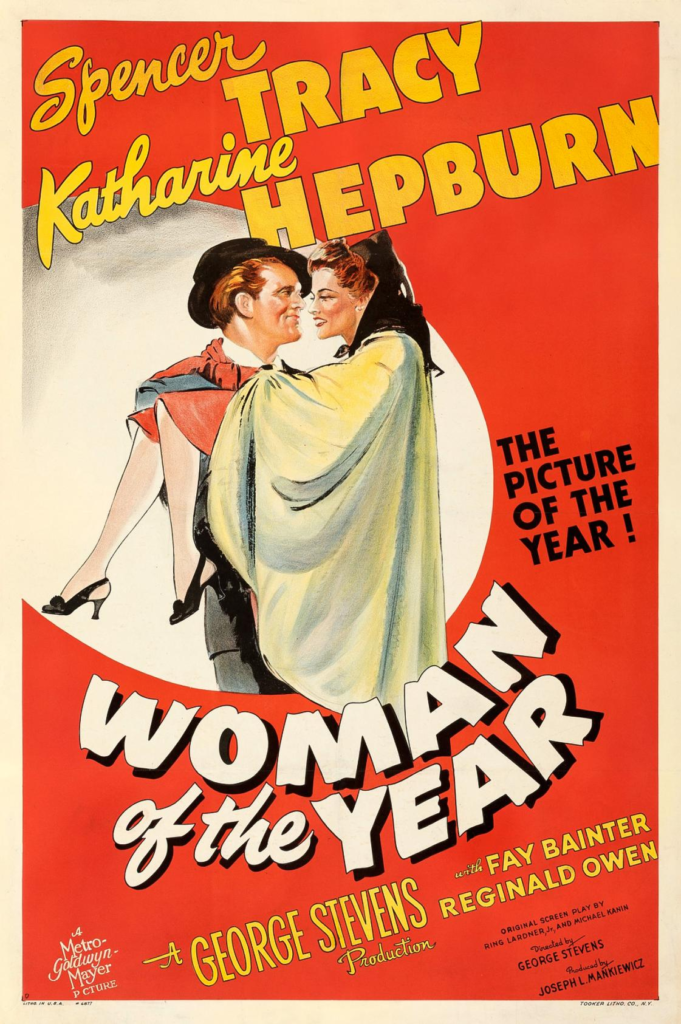

A (Kinda) Formalist Approach to Woman of the Year (1942)

Woman of the Year (1942) – Formalist (Kinda)

As teased last week, I went back to the Coolidge Corner Theater this week for another dose of that picturehouse goodness, seeing a film with a big audience. This week’s viewing was very different from last week’s more seriously toned The Defiant Ones (1958), but both do address very real, very serious social themes in their own ways, and I think quite progressively in each; with one about race and society and the other about marriage and women in society. And, interestingly enough, these two films had a crossover of themes, director, and cast when Spencer Tracy, Katharine Hepburn, and Sidney Poitier came together in Stanley Kramer’s Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967).

While Guess was Tracy and Hepburn’s final film together after decades of on-screen and real-world romance, this week’s film, George Stevens’s Woman of the Year (1942), was their first. And, much like in The Long, Hot Summer (1958), Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward’s first film together, you can actively see them falling in love with each other. It’s quite something to watch two people pretending to be fake people in fake circumstances falling in love for real right before your eyes.

This week the Review Roulette wheel landed on Formalist for our approach, and I’m going to play fast and loose with that because there are a couple things I want to talk about that are a bit loosey goosey to the form.

Firstly, this movie is funny. Like laugh out loud funny. And it’s not funny in the droll, witty sense that I think is often imagined in, for instance, Hepburn’s transatlantic accent, although that humor definitely is there. It’s funny in a very particularly dry, stupid, believable way, very much like another Catherine I wrote about recently, O’Hara in my review of Waiting for Guffman (1996). Both of these women offer sensational comedic performances seemingly effortlessly. There’s one scene I want to highlight for Hepburn that I think was truly comedically brilliant in a way that really surprised me, but first we’ll do a little summary.

For those unfamiliar, as I had been until last week, Woman of the Year is about how perfect and imperfect Tess Harding (Hepburn) is. Tess is an international affairs journalist at the New York Chronicle where Sam Craig (Tracy) is a sports reporter. The two have a spat through a few issues of the paper before they meet in person and instantly fall in love. After a brief whirlwind romance, they marry in an abrupt ceremony, soon finding out that whirlwind romances don’t necessarily make for lifelong romances between compatible partners. The majority of the film explores the pain of loneliness, isolationism, and desperation, while being riotously funny.

These discordant tones are extraordinarily balanced and the pacing is excellent. For instance, in a scene in which Hepburn is realizing she ruined their marriage – and, for the record, I do think she was wildly in the wrong – the camera holds on her while she listens to the words of someone else’s marriage ceremony. It stays on her face as she begins to really hear the vows she took, and as her wrongs dawn on her, her eyes slowly begin to tear and an almost imperceptible change in the muscles of her face rip your heart to shreds. What an actress.

Immediately following that deeply emotional silent character development, we get the comedic scene that finishes the film. It’s not really a spoiler to say that Tess and Sam end up together; it’s a rom-com and she does need to fully be the Woman of the Year by the end. But the way she achieves this? I try not to recommend films because everyone has different tastes, but if you are at all interested in comedy through history, you should watch this film. Every beat of this film builds up to an about 12-minutes silent slapstick routine with Hepburn solo in a kitchen, and because it has been built to and because it is the summation of every tone shift, marital problem, gender dynamic, feminist question posed in the film, it’s utter genius.

So, Tess realizes that she messed up very badly by thinking a marriage was just another thing she could dominate and be the best at, right? She was self-serving in her marriage (not necessarily selfish, but self-serving), so she makes the decision to show Sam that she has changed by serving him breakfast. She wants to be the perfect wife, so does all the things she thinks a perfect wife does.

Side bar: in my book, chapter 3 has a case study on changes in dating and marriage dynamics in the post-war Christmas films I studied. To briefly summarize, the 40s films have very agential women – Mary (Donna Reed) in It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) buying a house without telling her husband, becoming an old maid in Pottersville as she told George she would if she couldn’t marry him, and saving the day; Doris (Maureen O’Hara) in Miracle on 34th Street (1947) being a divorcee, single mother, and seemingly VP of the flagship store for Macy’s in Manhattan; etc. – and the 50s films have women rigorously studying women’s magazines for how they’re supposed to act to be the perfect submissive wife – Susan (Debbie Reynolds) studying and practicing her husband’s interests for literal months in the hopes of convincing him she is perfect.

So, Tess has a similar idea: she’s seen from afar what a wife “should” do, and she tries to mimic that. Everything goes drastically but subtly wrong in this impeccable, long, silent scene of her just trying to make breakfast. The blocking is even impeccable because she’s working at the stove, counter, and table so there are different areas on screen at different times, and the longer it goes on, the easier it is to forget that one thing is just bubbling away off-screen until you catch a glimpse of it in the background of other shots. You can find part of it online, but it’s really so much better when you watch the whole film before – I know because I showed it to Ben when I got home, and found myself wanting to explain all of the context for why it was so funny. It’s Catherine O’Hara’s folded cheese but solo and for 12 minutes. Terrible-chef’s kiss.

There’s even one part in particular, several minutes into this domestic tragicomedy, in which she sports a triumphant smirk like she’s figured it all out while doing the dumbest shit trying to separate eggs. Oh man, Katharine Hepburn is perfect.

So, anyway, she nails the comedy and the emotional heartbreak long take. The other thing I wanted to comment on was how the audience reacted to it. One of the finest joys in life, for me, is sharing human reactions with strangers in a cinema. There’s something really special about watching a film in a dark cinema that pauses the outside world; we are all here to experience a work of art in a space made completely separate from all else. And for that extended period of limbo, we get to share the most human experience of feeling something. And for Woman of the Year that was so many things.

We felt beauty, love, adoration, sadness, empathy, compassion, disbelief, and joy. So much joy. Hearing all of these reactions from my fellow film-goers added so much to the experience, and I can’t help but think how important it was for Americans especially in the first year of their involvement in World War II to have a space in which they could pause all else, and focus on these emotions together. We, of course, have the bonus of retrospection, knowing that the two leads would go on to have a long, complicatedly human but true love affair; we get to knowingly see the moment two lives were changed forever in a love that rippled challenging consequences and invigorating influences for millions more. But sharing that experience with strangers who just came to enjoy some art really is a top tier reason to be alive for me.

As I said about Catherine O’Hara & Co., we were blessed to live at the same time as them, and with Hepburn, I’ll add that we are so lucky to have her work available to us. The Philadelphia Story (1940) is one of my favorite films of all time, and I would now add Woman of the Year somewhere a little further down that list. She’s a damn delight, AND she’s a badass woman. The more you read about Katharine Hepburn, the more you want to become her. She’s on list after list of Women of the Century, Women Who Changed the World, Icons (genderless!!) of the Century, etc. etc. etc. All of that and a flawless 12-minute silent slapstick scene? She really is a Woman of All Time.

Because I’m Never Done When I Say I Am

Feminist

Just to briefly add to that final paragraph and our retrospection, we get to know a lot of the amazing impacts Hepburn’s life had and we get to see her as a stand-out star who never relied on her beauty to get through a scene without something deeper being conveyed. Her performances had layers and layers of subtext and independent confidence that emanated her strong-willed, still soft, feminine power.

In Woman of the Year, Tess sees herself in the shadow of only one person, her Aunt Edith, a feminist icon in her own right. In real life, Hepburn’s mother was a married feminist campaigner herself, and she and her husband were both social activists. They raised their children to think for themselves, exercise their free speech, and fight for what they believe in. For instance, as a child, Hepburn would put on performances for family, friends, and neighbors, charging a ticket fee to raise money for the Navajo people. Hepburn certainly drew on her own adoration of her mother especially for the role of Tess looking up to her aunt.

What I think is quite wonderful about this film is that it offers two examples of how strong independent women can also be wives without sacrificing everything. I will admit that I was very concerned about the direction the film was going in up to and including the hilarious 12-minute kitchen scene, but Tracy’s character delivers a single line that redeems the film fully. I guess this is a spoiler, but he says to her: “I don’t want to be married to Tess Harding any more than I want you to be just Mrs. Sam Craig. Why can’t you be Tess Harding Craig?” And in that moment, is when I think Katharine Hepburn fell in love with Spencer Tracy. He says that line with conviction.

Leave a Reply