A Formalist Approach to The Sting (1973)

The Sting (1973) – Formalist

This may come as a shock to you, my dear readers, but I’m not too partial to fascism. I’m not super keen on a crackdown on free speech or the power of the federal government getting behind a consolidation of media into the hands of a few. I wrote about those things: this past week in an article for Clio & the Contemporary and in my book, out in just over four weeks.

No one wins from our cultural media being controlled by five of the worst guy you’ve ever met except for those five bitches, their shareholders, and our fascist leaders whose narratives get pumped into your screens on every major streaming service that you passively watch between overtime shifts to make up the difference in your monthly costs since his royal dipshit took office. But that’s why we’re here, right? I’m here, you’re here, and we’re both acknowledging the importance of that cultural media and being able to critically analyze it, not just take in their lazy propaganda slop force fed into us all like little foie gras ducks fattened up for fascists’ dinner in a ballroom that only costs the median weekly income of 165,837 Americans ($200 million/$1,206 weekly) or less than a third of Elon Musk’s (as of January).

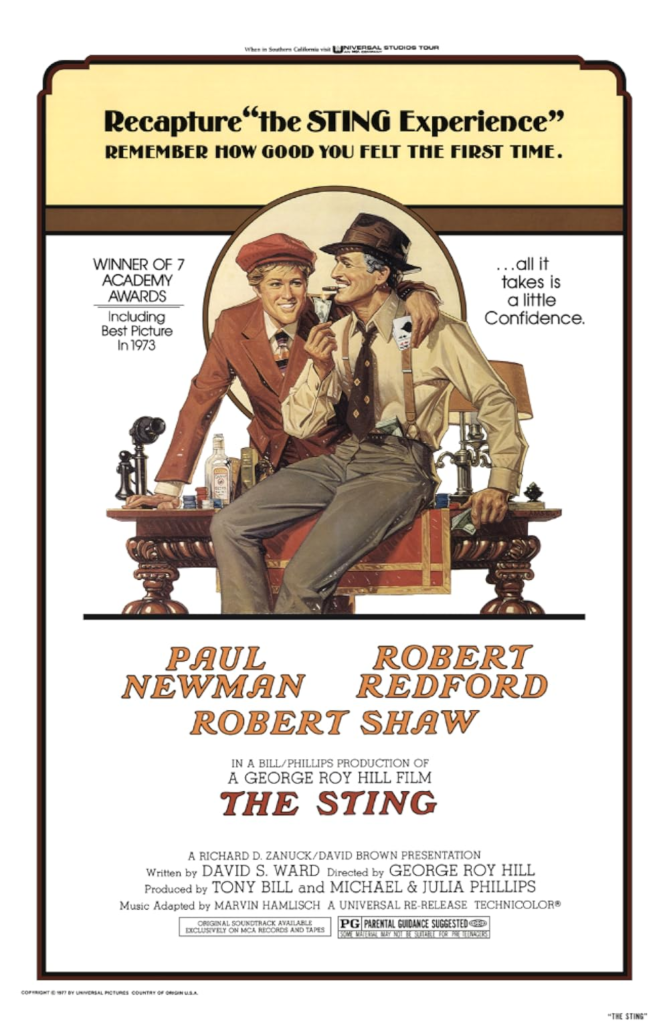

One of the things we lose when five Walgreens-brand douches take over the creative cultural sector is rich, vibrant, interesting cinema. Sadly, this week we lost a real star who made such cinema, so in honor of the late Robert Redford, and to turn this sad ass intro around into a celebration of the unique and beautiful, let’s talk about a wonderful film: George Roy Hill’s The Sting (1973).

Let’s just get it out of the way early: Paul Newman and Robert Redford are both in this film, and if you are a living, breathing person, you will at some point (or twenty) in this movie have to swallow hard and refocus on the plot. That’s the only detriment to this exceptional film, and, honestly, is it?

Side bar: the first person to ever ask me “Paul Newman or Robert Redford?” is the person who broke the news to me of Redford’s passing, and we both said our RIPs and then, “respectfully, still Newman, tho.”

Anyway, banger of a film about two conmen taking down bad guy Robert Shaw in an extremely elaborate gambling scheme. A million times better than the original Ocean’s Eleven (1960) which is just the Rat Pack getting paid a whole lot of money to hang out and is like 90% phone calls between them for some reason. The Sting is action and comedy and Newman and Redford and poker terms I don’t understand and Newman and clever cons and Redford and Newman. It’s a god damn delight.

Not only is the con super enjoyable, but the whole structure of the film is so creative, we have to talk about it. I fudged the Review Roulette wheel this week because I want to talk about this structure, so we’re doing Formalist as our approach.

The Sting is set in 1936 depression era Joliet, Illinois and eventually Chicago (where we were last week for The Blues Brothers too, albeit 44 years later). It opens with an old school Universal Pictures logo, “The Entertainer” playing, and title cards that upend the whole film before it even begins.

In the first card, we see drawn depictions of Newman, Redford, and Shaw with their names on the left side. The three main characters are situated at a drugstore counter, and we’re not quite sure what their relationship is, but Redford looks like he might be intimidating Newman at the behest of Shaw. Newman is holding a newspaper with a headline about the Spanish Civil War placing us temporally. Next card? A film crew, lights, camera, the whole shebang around the image from the first card. Now, is this brilliant or is this just the card for the production team and director’s credit? I don’t know, maybe we should go to the next car— what’s that? A THIRD LAYER of the writer writing the scene the film crew are producing next to the title and his own credit? Surely, this is just a clever use of opening credits to say “this is a film and these are some of the layers of how a film is made.” Or is it? Next card is a title card reading “The Players” with disembodied hands holding a comedy and tragedy mask each. Then we get the actors in live action shots from the film we’re about to watch, starting off with our first shot of Newman’s baby blues, then Redford’s goofy charm, and whoever else is in this movie before a setting label (Joliet, Illinois) and a scan of a Depression-era street. The film takes off from here.

Now, I was like “that was a cute little opening, fun way to place us in time and shout out the crew. Film crews and writers deserve more pomp and praise.” But then, once everyone is established and the film is off and running and you’re into it fully because now we’ve gotten Redford in a room with Newman in the latter’s dual business brothel/carousel for all the merriest go-rounds a person could want, we get another title card. “WHAT?” you gasp, “Another title card? And one reading ‘the setup?’ Were the opening credits a curtain raising the fourth wall?” And then I noticed the silent scenes. This film is brilliant.

So throughout the film, there are act breaks to guide the audience through a complicated con with multiple stages. We see a whole set being built, auditions, costumes, a career conman who brought his own resume and props. It’s essentially a staged play being produced before our film camera eyes, which themselves only allow us to see what the director wants us to. The film is kind of a mind fuck actually.

The core plot plays straight, you can follow it, it’s so well-conceived and executed, and truly one of the best laid plots I’ve ever seen. It has layer upon layer of self-interest and misdirection, and I did not see the ending coming, it’s that well done. So, straightforwardly, there’s already so much to appreciate about the creativity of this film.

When you start to peel back the layers of production, though, it gets even better. It’s a film that knows it’s a production. The players are actors playing conmen who are actors playing gamblers who collectively are playing (in the con sense) Robert Shaw who is playing Redford who is playing Newman who is playing the feds, and all of them, because of the clever silent film scenes and the title cards, are seemingly aware that they are acting. Robert Redford even says at one point “just let me finish the play.” And that implication, that these men are all aware they are entertainers, per the song, throws into question the whole profession of acting as a con. And, speaking personally, there is no better way to make a film than to embed a subtext that says, “is this all bullshit?” I’m gonna see that film 100% of the time.

The Sting is so successfully playful with the loosey goosey relationship it has with concepts in cinema that it becomes a masterclass in cinema itself. Maybe cinema is a con because it’s guiding its audience to a conclusion with sleight of hand tricks, fancy costumes, insinuation, and Paul Newman that distract the viewer while that subtext plays out. Maybe it’s worth it to think about media in that way, that it’s a smokescreen and the audience is a mark. I, personally, do think that approach is helpful, especially when it comes to propaganda and analysis, to deconstruct the messages of a film and understand the choices made in producing it. Or maybe it’s just a really playful way to make a film about an over-produced elaborate scheme to fuck over Robert Shaw worse than Jaws would a few years later. All are valid reader responses and takeaways from the film, and I think all are also worth thinking about.

Anyway, it’s a phenomenal film and not just because of Paul Newman’s cunty little mustache.

Because I’m Never Done When I Say I Am

Comparative

I’m adding a category here, because guess what? Last week’s Blues Brothers review was my 75th film review on Review Roulette!!! I will soon add it to our methodology when I introduce Review Roulette’s new home on a site I am building for my husband’s and my public scholarship. More on that soon, but first, I want to draw some comparisons between The Sting and White Men Can’t Jump (1992). Both films are about conmen hustling their way through life and compromising their personal relationships as they go. They both have interesting commentaries on class dynamics and wealth as power, and they both use music and sound so exceptionally that they should be taught in a film theory class together. A real fascinating pair of films together.

Leave a Reply