A Textual Approach to Dear God (1996)

Dear God (1996) – Textual

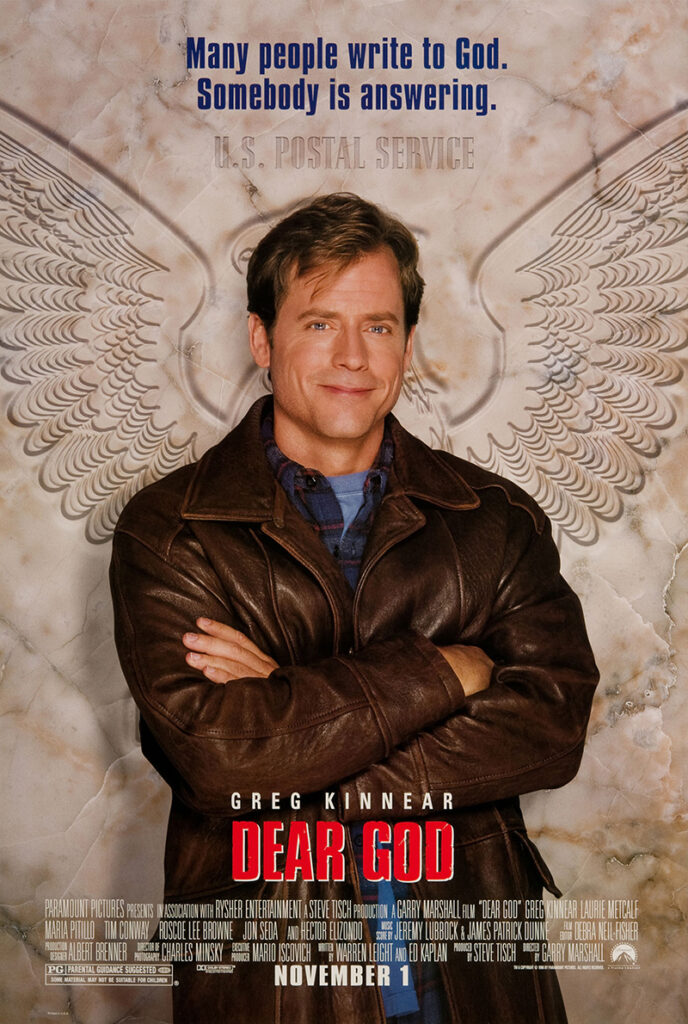

Anyone else saying “Dear God” more in recent weeks than ever before? Yeah, me too. So much so that it reminded me of a film I watched as a kid and really loved because I had a childhood crush on Greg Kinnear, as I’m sure most people did in the 90s.

So, this week I watched Garry Marshall’s Dear God (1996) to shift my horrified “dear God”s into more productive “dear Gods”. Now, to clarify, many of you may know that I am not a member of any organized religion; I believe my relationship to the spiritual is mine and mine alone, as yours is yours and yours alone, so, not to get too into it here, but the “God” I am addressing in my own “dear Gods” is the divine in all of us, goodwill and love for your fellow man. This is not going to be a religious review based on any established organized religion or their canonical views; it is simply humanistic.

The Review Roulette wheel landed on Textual for our approach, which, as a reminder, I use here in Review Roulette to look at the literal text of the script, the words and dialogue in the film. Yes, I know that is not standard; no, I do not care.

So, for those who haven’t seen this delightful little film, it’s Meet John Doe (1941) mixed with Miracle on 34th Street but the Kris Kringle figure, Tom (Kinnear), is a conman sentenced to work for a full year to understand the value of a dollar. To fulfill this sentence, Tom gets a job with the US Postal Service as a mail sorter in the dead letters office where the “Dear God” pile sits unread. With extremely thin reasoning – even films we love can have nonsensical, illogical leaps from A to B, and that’s okay – Tom starts to read the letters and accidentally do good deeds, aided by his incredibly diverse colleagues. Gradually and with their encouragement, he commits to purposefully doing good deeds and a movement begins to spread of people being kinder to one another, random acts of kindness and “miracles” abound. Tom, of course, is put on trial for opening mail that wasn’t addressed to him, but the day is saved by a postal strike at Christmas with USPS carriers refusing to deliver the mail as long as Tom is on trial.

I love this movie, and I loved it as a kid, too. There’s something so simple and joyous about it that I think we all could use right now, and there are a few lines in particular that capture that. So, let’s dive into a few quotes that we can read as secular gospel for the soul.

Throughout the film is an undercurrent of class consciousness, intersectional solidarity, and active citizenship, not unlike the kind I wrote extensively about in my Capra series that that Meet John Doe review is a part of. In fact, actually, I would say that Dear God is Garry Marshall’s most Frank Capra-esque film, which is probably why I love it so much – two of my favorite directors meeting in the middle with a corny ass 90s film? Straight to my veins.

This social messaging is conveyed through a recurring engagement with the idea of the “haves and the have-nots”. When his colleagues are trying to convince him that they should actively start answering these letters, Tom scoffs at the idea, saying, “See, the haves help the have-nots, and I hate to disappoint you, but we’re the have-nots.” Later, the high-strung former lawyer Rebecca (Laurie Metcalf), returns to this idea, arguing, “The have-nots have got to do it. The haves haven’t helped anybody but themselves since the 70s!”

So, Tom is operating in a trickle-down economics way because all he has ever known is a struggle. His dad left when he was a kid, he’s the sole carer for his mom, and he has only ever stolen from the haves, gambling what he doesn’t need for survival. At about 35 in the mid 90s, his adulthood has largely been dominated by the 1980s and Reaganomics, leaving him feeling helpless, bitter, and economically disadvantaged, all part of the goal of the trickle-down idea with its illusion of the have-nots ultimate reliance on the haves.

This film breaks that illusion, shatters the distorted glass of the economic fun house mirror propped up in the cheaply outfitted haunted house that was the Reagan administration, and says, “actually, if the have-nots don’t step up, the haves will destroy us all.” And, I don’t know, I feel like that’s a pretty god damn important message for 1996, and also, perhaps, 30 years later.

Later in the film, Héctor Elizondo, Garry Marshall’s and my main man, who plays Vladek, the Russian boss of the post office, takes the stand to defend Tom’s actions. Vladek argues that while the letters were addressed to “God”, “God” lives in all of us:

Vladek: I do believe that God also lives within each of us.

Prosecutor (Sam McMurray): Is this going somewhere?

V: Perhaps He does not live within lawyers. But I believe that God was speaking through Tom. Tom Turner made ordinary people do extraordinary things. We need this. As his supervisor, I covered up for him. Therefore, I am as guilty as him.

Ultimately this is not the final argument that frees Tom, but it could have been. I commend the movie for not stopping here and instead having a blockade and strike instigate his absolution because that show of solidarity is beautiful, but I will not knock Vladek’s argument. I think it’s flawless.

As I argue in my book (I know, I can’t help myself), Miracle on 34th Street is a film prompting us to reflect on who we have been and who we would like to become. We have a whole city brought to a stand still to decide in a court room if New York, and the US more widely, wants to have a society where we believe that generosity and kindness are good, actually; if believing in Santa might actually tell us more about ourselves than about him; if we want to have faith in a being that is purely good even without a profit motive. Dear God does something similar, putting on trial not the idea of Santa Claus as a mythic figure of goodness, but a real man and the question of whether “God” lives in all of us.

Again, I am not a religious person, and I invite you to interpret that in whatever way makes sense for you personally. For me, it’s Vladek’s argument. Who “God” is and how “God” manifests are irrelevant to me. The question is if we want to live in a society in which we all are responsible for one another’s well-being, if we are each the creator of the divine in others, if we have an active duty to our fellow man to work in his best interest, and if we all are then understood to be each other’s keeper.

There’s an old joke or parable, depending on your context, about a guy stuck on a roof in a flood. A man in a boat comes to him and says, “I’m here to rescue you, hop in,” and the guy says, “no, thank you. I prayed to God, he’ll save me.” A little later, the guy is getting hot, hungry, and thirsty when a helicopter drops a ladder to the roof with a soldier saying, “I’m here to rescue you, climb up,” and the guy says, “no, thank you. I prayed to God, he’ll save me.” Eventually the guy dies from exposure, starvation, dehydration, you name it on the roof, and when he gets to Heaven, he’s livid, and he’s like “God, what happened? I prayed to you and you didn’t save me,” and God says, “I sent a boat and a helicopter, what more do you want from me?” And I think that applies here, however that parable works for you in your own faith or spirituality. For me, it’s that we are each other’s salvation.

Of course, as Sartre noted, we are also each other’s damnation. Hell is in fact other people as we are seeing in seemingly constant streams these days. Every minute of every day is filled with acts of evil perpetrated by the vile clowns tapping into the worst impulses, fears, and animalistic violence humanity has to offer. Which is why films like Dear God are so important.

There’s something life affirming in watching others do good deeds. It’s both the plot of the film and the film’s impact, inspiring others to random or targeted acts of kindness. Salvation and damnation live in all of us, we are all theoretically capable of both, and it is a choice which we nurture, nourish, and practice. And I implore you to nourish the salvation. Do good deeds and post them on social media. Be loud about how you help people. Peer pressure people into kindness. We must counteract the streams of evil flooding our feeds, eyes, and ears; we must fill those things with compassion, love, generosity, and kindness. Because no matter how bad things get, you can always offer someone a boat.

On a final note, I want to emphasize again that the collection of people making miracles for strangers, the God Squad as they are dubbed, is incredibly diverse. They are different ethnicities, religions, classes, ages, and genders simply trying to help people. Whether it’s offering to watch an overworked mom’s kid for a few hours or cleaning an exhausted cleaner’s own home or saving a man from ending his own life, the have-nots show up how they can with what they can. They assess their skills, their resources, and their time, and they show up for one another. And I think that’s an incredibly valuable depiction on screen. Dear God has abysmal reviews because people can’t see past what they think a good movie should be, and I think that says more about them than it does about this film.

Leave a Reply