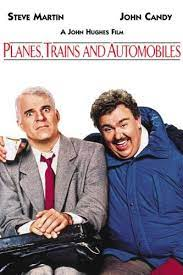

An Apparatus Approach to Planes, Trains & Automobiles (1987)

Planes, Trains & Automobiles (1987) – Apparatus

Hopefully your Thanksgiving commute will not be as hectic and fraught as Steve Martin’s and John Candy’s in John Hughes’s Planes, Trains & Automobiles (1987), but here’s a quick read for your journey either way. The Review Roulette wheel turned out Apparatus as our approach this week which, admittedly, I had to think about for a sec before realising the entire film is indirectly a condemnation of the entire transportation structure of the US, i.e. one of my favourite topics to discuss. So, let’s hop on a bus and talk about how this film makes a universal comedy of the US’s dire lack of public resources.

I had never seen this film, but because I live in our society and have seen other travelling-to-a-destination-with-a-tight-ass-and-an-eccentric-annoying-stranger-with-a-tragic-backstory-all-on-a-strict-schedule movies, I felt like I had. The story has been used and abused so many times, and I’d bet that this is not even the earliest example of the tropes, but this is one of the most widely known and a rare Thanksgiving film. Most of the beats of this film, even if you’d not seen it, you’d recognise: they get on their first mode of transport as tensions rise between them, that mode fails in some way and drops them at a secondary location so they must then figure out different modes of transportation to get to their destination. Here, Neal and Del (Martin and Candy) start in New York, head for Chicago, but end up in Wichita, Kansas due to a snowstorm in Chicago diverting their landing.

The film is a fun comedy of opposites attracting and leans into the interaction between two people of different economic classes: Neal an obviously wealthy marketing executive who commutes between Chicago and New York for work, and Del a travelling shower hook salesman. Their personalities are stereotypical of their classes and professions in that Neal is arrogant and stuck up and Del is gregarious and overly friendly to the point of being inconsiderate. A large part of the comedy, however, comes not from this interaction between them but from Neal’s discomfort with taking public transit as a wealthier person.

Something not frequently recognised in the US is that planes are public transit, no different from privately owned bus and train services, but for some reason they are a more socially acceptable form of public transit. Maybe it’s the price that precludes the poorest in society from travelling via plane frequently, or that it’s a more convenient mode of transport across oceans and continents, but flying is an actually socially respected form of public transportation that even buys you cultural capital for taking. But even on a plane there are levels to class and comfort, and when Neal is bumped from his first-class seat to sit in economy next to Del, he is livid and visibly uncomfortable the entire time for comedic effect.

On the other end of the financial spectrum of public transportation taken in this film is the interstate bus. Neal is indignant, absolutely disgusted with how close he is sitting to poor people who chose this as their primary mode of transportation while he is on his fourth having been degraded so low as to step foot on a bus. Del is perfectly comfortable, having travelled by bus for work before and feeling no stigma having to do so again. He rouses the bus brimming with passengers in travelling songs to pass the time, something Neal attempts to join in on, starting to sing a song inappropriate for the moment and crowd who do not know it (Frank Sinatra’s “Three Coins in a Fountain”) suggesting a class division along cultural lines as well.

Beyond Neal’s discomfort with public transit, which, in order to be played for a laugh needs to be relatable with the audience and therefore reflects some level of socially acceptable class discrimination attributed to those who take public transportation, the film also comedically shows how abysmal public transit options were and still are in the US. In this film, there two take taxis, a plane, a pick-up truck, a train, buses, rental cars, a milk truck, and the Chicago L metro system to get home. Obviously, the US is a gigantic place and not everywhere can be connected to everywhere else by easy and immediate transit links. It is telling though that in order to get to the closest possible transit links, even John Hughes had to throw in the random car by circumstance every once in a while.

In one scene, when Neal sets off to get a rental car, it isn’t in the spot where the airport shuttle dropped him to pick it up. With the shuttle having left, he is forced to walk three and a half miles down a highway and across a runway to get back to the rental car desk. Most airports have this set up, sure, but so do most cities. The fact he had to walk down a highway because he didn’t have a car and there was no other publicly accessible option to traverse the area is a condemnation of the lack of walkable spaces in the US and can be extracted from the film as a moment many Americans would and do experience without access to cars.

This film leans into the US’s lack of public resources as a comedic device and nearly 40 years on and scores of mimicking films later, it’s still completely accurate. So, whatever mode of transportation you are using on your Thanksgiving commute, please spare a thought for your own personal ideas about public transportation. If you have a car, do you prefer a car because it’s frequently the most convenient for point-to-point transportation in the US? Is there a class dimension possibly stemming from the American Dream idea that to be a success you must own a car as a status symbol and upgrade it regularly for clout? Do you despise that idea? Do you think taking public transit is something for other people to do or do you take the bus or train and support the system when you can? Do you regularly take public transportation by necessity or preference? Do you think public transit should be nationalised or more heavily invested in as a public good? Would you prefer more public transit options for traversing the country that are not by car or flying?

I want to make it clear that there’s no judgment here. I do not drive for medical reasons, so I have always taken public transportation around the US and Europe, and I have a certain perspective on it. But I also certainly had to unlearn particular prejudices I was raised with around public transit just by growing up in the suburbs of an American city. So please do not take offence at these probing questions that I used to challenge my own stance, but please do take the opportunity to reflect on your own ideas that you may never have questioned before. Looking at public resources and infrastructure in films and reflecting on how they are portrayed is an excellent way to spark harder equity and justice conversations in our world outside of the film. We can use films like Planes, Trains & Automobiles to think about the structures of our society and challenge the things in our lives we take for granted or as a given for our social and economic situations.

Because I’m Never Done When I Say I Am

Auteur

John Hughes is such an interesting director. He frequently explores suburban identities and class dimensions, and this film is no different, fitting right into that corpus of work. One thing that stuck out to me (the Christmas film studier) is that Neal’s house here is also Kevin McCallister’s (Macaulay Culkin) house in Home Alone (1990). When directors use the same locations or indicators of wealth across films, it could be for convenience and price, but we can also, as critics, draw connections between the statements on wealth made using those same touchpoints. With both of these being holiday films and both centring on being resourceful in the face of displacement from one’s family, this mansion offers an interesting rock as a place to get back to by all means. Del on the other hand has no home to return to at all, a decision for the character which has overtones of financial circumstance – he cannot afford a home – when the more likely reason is that he is a travelling salesman and, after the reveal of his tragic backstory, he may not have a settled home by choice. The financial and family security and the security of wealth and resources embedded in Neal’s (and Kevin’s) home, especially in comparison to Del’s situation, are fascinating commentaries on class divisions in the US and in our media.

Leave a Reply