A Contextual History Approach to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Next (1975)

[Content Warning: Mention of suicide]

[Contains light spoilers]

One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) – Contextual History

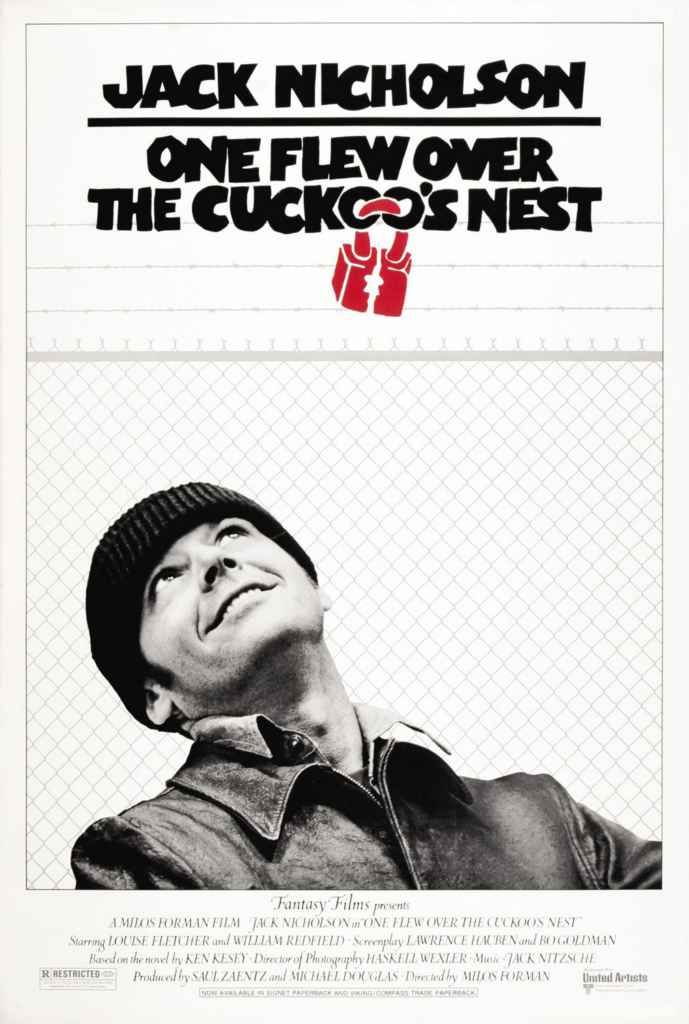

Today, my lovely loyal readers, is a special day because it is my 50th(!!!) film review on Review Roulette. To celebrate, this week I am reviewing a film that turns 50 this year (and which I had never seen before): Miloš Forman’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975).

I had an interesting reaction to this film, and I want to walk through the development of my thoughts even more than I normally do in these reviews. As this is our 50th film and as my goal with Review Roulette is to open up people’s minds to different ways of interpreting media, I think this is a really excellent example of a deeply complex film that deserves an equal complexity of thought. So, bear with me as we delve into a wonderfully layered and complicated film.

I often say here that I was aware of a film or plot line just by virtue of living in society, but my assumptions about this film were wildly off the mark for some reason, so for those who have not seen it: One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is about a mental health facility into which the incarcerated R.P. “Mac” McMurphy (Jack Nicholson) is transferred after faking a mental illness to get out of work detail. Mac is a scoundrel who sarcastically declares himself a “god damn marvel of modern science”, takes it upon himself to harass the ward’s overseer Nurse Ratched (Louise Fletcher), and enlists other patients to cause trouble and aid him in his many attempts to escape.

The Review Roulette wheel landed on Contextual History as our approach this week which I initially felt a bit uneasy about. I have researched developments in psychoanalysis in the post-war period and even at one point wanted to do my PhD on mid-century psychedelic research, but the actual state of psychiatric facilities in this period is not my strong suit. But as I watched the film with this in mind, I found I had many more observations about temporal markers in the film widely, and I came to the conclusion that I think One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is one of the most 20th century American films I can think of.

My thoughts on it developed chronologically backwards as I thought more about the film and read about the 1962 Ken Kesey novel it was based on. As I thought more on miniscule details that complicated my surface-level perception, I began to see how multi-generational the story was and how clashes between those generations (as represented by certain characters) reflected an American struggle over time that I had not considered before.

Initially, I felt the overwhelming 1970s Hollywood sheen of male frustration at women and society. It took me a while to get through my own frustration with that sheen as the film centers the dichotomy of Mac and Nurse Ratched so prominently: she is a dictator confining men and dominating them with her structured systems, rules, and expectations of decorum while he is her fool freeing men of their chains and reintroducing them to male joy and activities traditionally associated with it (e.g. watching the World Series, fishing, gambling, drinking, and sex). The dictator and the fool dynamic at two extremes on the spectrum of control is a classic trope, and the added elements of their genders and the film choosing the setting of 1963 (after the novel was published) felt to me like direct references to backlash against the feminist movement, namely Betty Friedan’s 1963 The Feminine Mystique.

So, I was consumed with this perspective of 1970s misogyny, and I want to pause here because this was a very helpful moment for me in how I construct my reviews. Part of my reasoning for starting Review Roulette is that I can’t stand surface-level film reviews. Oftentimes, reviewers have very tight turn-arounds to publish reviews in more traditional publications and, in my opinion, that can result in more basic perceptions or “hot takes” that run the risk of missing nuance or purpose in that film. That doesn’t mean that our first reactions are wrong necessarily, but it does mean that, especially with multi-layered films, investigating why you had the reaction you did can be really helpful in developing a more solid perception of the media you are interrogating.

This 70s misogyny is undoubtedly in the film, and I was reacting to it because of both the cultural assumptions I had about the villainization of Nurse Ratched and the fact that I watched it for the first time in 2025. I am not the target audience Forman had in mind when adapting the novel, and that’s absolutely fine, but it did color my initial perception of the film and realizing my presentist reading prompted me to try to look beyond it. When I turned to the novel, it became clear that the book includes the gendered struggle for domination of the ward but that that was not the main focus of the book. The book is far more about the state of psychiatric facilities in the mid-century and their symbolism as bureaucratic institutions acting as authority figures to confine and control a population. Those ideas are also in the film, but are diluted, for me, by the prominence of the gendered dichotomy of Mac and Ratched. And I think that that is fascinating. My view of this film is not that of the overwhelming majority, I am aware, and that’s what’s so great about art, right?

Let’s be clear, though, I thoroughly enjoyed this movie; I just felt it was far more about men being oppressed by women than people in general being oppressed by society. The dilution of the deinstitutionalization, anti-establishment themes in the book is also a deliberate choice by the filmmakers as large parts of the story are lost in the film. One of these omissions is the significance of the role of Chief Bromden (Will Sampson), the Native American narrator of the book whose perspective and life story of cultural and political oppression serve to build the multiple dimensions of the themes of domination and control. In the film with an omniscient camera serving as a visual narrator, we lose that depth of his character and the foundations of his ancestral traumas at the hands of the US government as a real-world example of the simulated oppressive system within the ward.

So, I think the film is very 70s in foregrounding the masculine oppression by a female character, but it’s set in 1963. Here’s where the contextual history comes in. There are two layers here. Firstly, a little timeline:

- Kesey began writing the book in 1959

- It was published in 1962

- Kirk Douglas purchased the rights to adapt the story for Broadway and film in 1962

- The stage play debuted in 1963 starring Douglas

- Douglas couldn’t find a studio to back his adaptation throughout the 60s but hired Forman in 1969 to eventually direct

- Forman was trapped in the Eastern bloc in Prague where the Soviet Union cut his contact with Douglas and enacted the “normalization” process of concentrating power in Czechoslovakia

- Michael Douglas acquires the rights from his dad in 1971

- Forman flees the Soviet Union to the US in 1973

- The film is released in 1975

Obviously, that is extremely truncated, and you can read more about it elsewhere, but I highlight these things to show the influences on the film. It was made by rebels who fought against oppressive systems. Kirk Douglas very famously advocated for Dalton Trumbo to get writing credit on Spartacus in 1960, one of the final and biggest straws to break the Hollywood blacklist. Michael was a student activist against The Man™ in the late 60s (and went on to be an ardent activist). Forman escaped the Soviet Union. These experiences and many more from others working on the book, stage show, and film provide such varied and rich perspectives in the making of the film across generations, political landscapes, and cultural eras.

Secondly, the characters themselves represent different times. Mac is very firmly a post-beatnik radical. He’s edgy and contrarian and hates authority figures putting him down for “drinking and fucking too much”, but he’s also sensitive and thoughtful and wants to bring chaotic joy to the lives of his fellow patients. At one point, Mac fully escapes by hijacking the bus with those patients and taking them to a marina where they steal a boat to go fishing. Instead of leaving and securing his own freedom, Mac chooses to return the boat after their expedition and is re-incarcerated on the ward. Soon after, Mac learns that several of his friends are voluntary patients and he becomes irate that any of them would choose to be under the domination of Nurse Ratched, yet here he is after having chosen to return the boat. This to me is very much indicative of the early 1960s on the cusp of greater rebellion and counter-cultural revolution as the decade goes on.

On the flip, Mac’s foil, Nurse Ratched is more indicative of the early 1940s. She rules the ward with quiet fortitude and emotionally manipulates the men into staying in line. She seems battle-hardened and uses early 40s forms of psychoanalysis in group settings as her preferred therapy method. When this fails, she resorts to more torturous “treatments” such as electroconvulsive shock therapy and lobotomy. She echoes WWII in her vaguely dictatorial personality, her treatment methods, and her physical look with 40s hairstyle to boot. Putting the 60s character in direct opposition to the 40s character and having them rebel against each other in that dictator and her fool dichotomy of extremes I mentioned earlier is where I thought my real analysis would lie. It’s a fascinating thing to think about what commentary the 60s would have on the 40s through the lens of the 70s, but the extremes they represent are on a spectrum of control, and I think the more interesting analysis is of who they are controlling.

This brings us to the patients, specifically Chief Bromden and Billy Bibbit (Brad Dourif). I think all of the patients represent individuals in the 1950s being pressured to conform to socially conservative institutions and traditional domestic ideals such as heteronormative marriages and ages of consent. The Chief and Billy, however, offer two prominent examples of the influences Mac and Ratched can have.

Billy meets a very tragic end after being humiliated by both Mac and Ratched. The young man is peer pressured into having sex with a woman Mac sneaks into the ward, presumably losing his virginity to her as he has repeatedly insinuated that one must wait until marriage. When Ratched finds the two, she asks if he is ashamed and threatens to tell his mother, causing him to revert to a childlike state as he experiences a severe panic attack and ultimately dies by suicide. Billy is failed by both Ratched’s form of control (in the guise of protection by way of social decorum and conformity) and Mac’s form of control (in the guise of freedom by the way of social pressures to rebel).

The Chief, on the other hand, is radicalized to rebel against Ratched and with Mac. Mac inspires him to want to rebel while Ratched’s brutal humiliation of Billy drives the Chief to strength in anger. The Chief ultimately rises above the confines of his incarceration and the oppressive systems within the ward with two heroic acts at the end of the film.

Billy and the Chief are both presented as characters who are trying to find themselves within a system of conformity (either to Ratched’s social conventions or to Mac’s rebellion against them). Billy clearly requires some form of social structure and emotional support but cannot find a middle ground in the extremity of Ratched’s reign and the lawlessness of Mac’s mayhem. The Chief, on the other hand, finds his own path away from both of them but carrying elements of each.

And I think this is really the heart of this temporal framing of 40s, 50s, and 60s from a 70s perspective: expectations of conformity will either break an individual or break a window.

It’s a very 20th century American film, especially taken in context with its original book form. It’s layered and complicated and messy and contradictory and hypocritical and nuanced just like American history. To take this temporal reading a step further, the US in the 1950s is very much like one of those patients trapped in the middle of extremes vying for control, especially in that mid-century period when fearmongering, nuclear threats, and social pressure to not talk about any of it were so prominent. America was being redefined in our cultural media and on a global stage, and the people were still processing the crimes against humanity our nation committed in Japan while also setting off the Cold War.

And in a very complex way, I think One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest captures so much of this in those miniscule details that encouraged me to keep thinking beyond my first ideas. Spending the time to really think about what changes when we realize some of the patients are there voluntarily or what the extended shot on Ratched’s face means in each group therapy session or the look on Mac’s face when he realizes some of the patients are there because they need the support that he does not, deepens our interpretations of the film. And if I have done anything with these past 50 reviews, I hope I have encouraged you to sit with your initial perceptions of media and really interrogate them: why do you feel that way, what changes if we shift our lens a bit, what questions can and should we ask of films to really embrace that art form for the wealth of meaning it contains? And if you haven’t gotten that out of these reviews, then as Mac says, “But I tried didn’t I? God damnit. At least I did that.”

Next week’s edition will be a little different as we will return to our methodology and add a few new approaches to the mix, but I hope you have enjoyed these first 50. As always, thanks for reading and sharing and engaging with your own ideas!

Leave a Reply