An Alternate Reading of Casablanca (1942)

[Contains Spoilers]

Casablanca (1942) – An Alternate Reading

As I mentioned in last week’s Valentine’s Day post on independent filmmaker John Sayles, my husband and I like to think together. This does not mean that we always agree or convince each other of our opinions; rather it means that I have a partner whose brilliant analytical mind I get to pick to understand his cultural and world views and that he prompts me with perspectives and questions that inspire deeper reflections on my own ideas and interpretations. So, naturally, on Valentine’s Day, he and I went to The Brattle Theater to see Michael Curtiz’s Casablanca (1942) and then discussed the film over a delicious dinner of tapas and hot cocoa dessert.

While we were thinking together about Casablanca, I was thoroughly surprised to find that we had diverging opinions about the film’s ending, and the character of Ilsa (Ingrid Bergman) specifically. So, in place of an applied lens on the film, I wanted to give our two perspectives this week in a special edition of Review Roulette (that mimics last week’s, I know, but indulge me (it’s a romantic film) (we’ll get back to regularly scheduled programing soon)).

I want to start by saying that each of these perspectives is valid. Casablanca is a masterpiece of cinema in each of our opinions, and that means that it is complex (and we know how I feel about complexity as the reason for living (as I wrote last week)). Casablanca is an incredibly well-acted film with so many layers of meaning, and therefore so many layers of interpretation, so neither of us is wrong in viewing it in different ways; instead, both of us are right for thinking so deeply about the film at all.

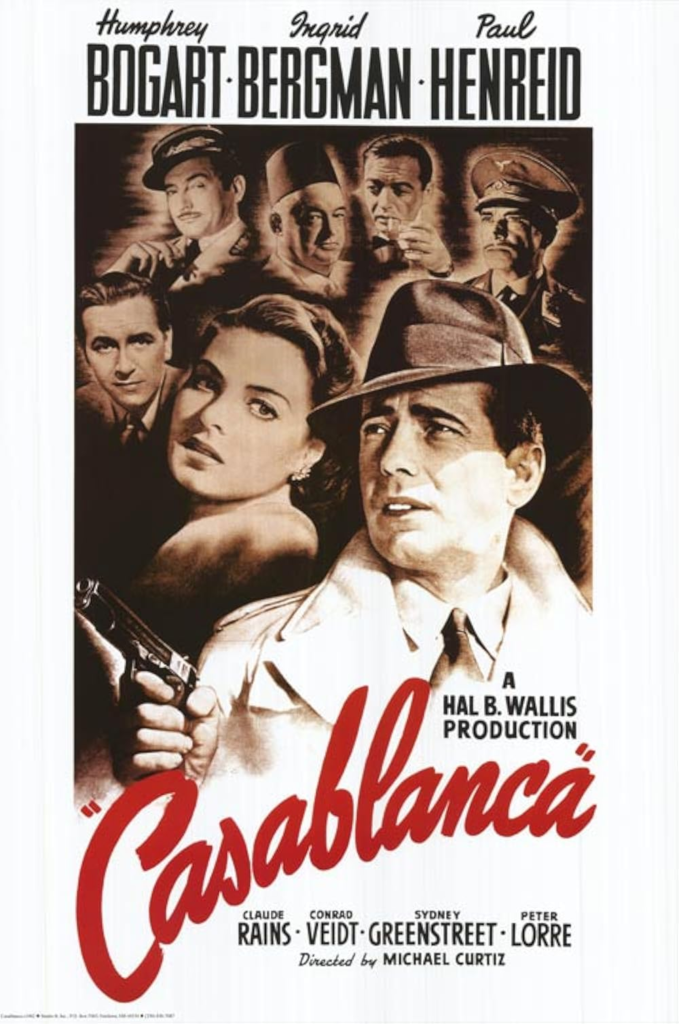

For those unfamiliar with Casablanca, the story centers physically on Rick’s bar in Casablanca, unoccupied French territory. Rick (Humphrey Bogart) suggests that he doesn’t stick his neck out for nobody, allegedly keeping his head down when Nazis, French, and Italian diplomats or generals come through. This suggestion is vague at best, as he refuses to allow known Nazis in his gambling hall, though they are allowed in the open bar area. When Victor Laszlo (Paul Henreid) arrives in Casablanca, seeking passage to Lisbon and then on to America, his presence causes a stir for the Nazis in town and his wife’s, Ilsa, causes one for Rick. Victor is an international leader of the resistance movement against the Nazis and has evaded the Nazis ever since his escape from a concentration camp earlier in the war. Meanwhile during his incarceration and while Ilsa thought her husband to be dead, Rick and Ilsa had a whirlwind romance in Paris just before the Nazis began their occupation 1940. This romance was predicated on the promise that neither would ask any questions about the other but ended abruptly when Rick asked Ilsa to come with him to Marseilles to both flee the Nazis and marry him. Ilsa sends a note in her stead telling him she cannot come with him and that she will never see him again with no other explanation.

In the end, Rick is the only person standing in the way of a safe escape for both Victor and Ilsa, the latter of whom comes to him to explain why she left Rick and Paris and why it is vital that her husband survive. After trying several tricks to get the travel papers from Rick, including holding a gun to him, she tells Rick that she still loves him and that she cannot leave him again, so long as he puts her husband on the plane to Lisbon, ultimately asking him to think for the both of them. At the airport, the final scene of the film and arguably the most famous romantic scene in American cinema, Rick tells Ilsa that the plan has changed and he fixed it so Victor and she could escape, leaving him to fight on in Casablanca.

This is the point my husband and I diverge:

My Husband’s Original Reading

In my husband’s reading of the ending, which I think is the far more common reading, Ilsa has gone to Rick and truthfully expressed her love for him and is honest when she says that she will not be able to leave him again. When she asks him to think for both of them, and inspired in part by an earlier conversation Rick has with Victor about Victor’s love for his wife, Rick makes the decision for all three of them. He comes to the realization that Ilsa is both a romantic partner and a muse not only for Victor and his resistance work but also for Rick and his. We are repeatedly told that Rick cannot return to America for an undisclosed reason, but after his departure from the US, we know that he ran guns for the underdogs in Ethiopia and fought with the anti-fascists in Spain. Having taken a brief hiatus from this work as he opened Rick’s and tried to harden his broken heart, Rick is reminded of the significance of fighting back having been inspired by both Victor and Ilsa. His decision to put Ilsa on the plane, therefore, is made because he knows that Ilsa will be beneficial to Victor’s public ideological work and that she equally will not be able to follow him in his more covert, physical, potentially violent work.

This reading, ultimately, is patronizing towards Ilsa and was a point of criticism of the film overall for my husband who admires the character development for Ilsa throughout the rest of the film. Ilsa displays so much strength in facing serious hardships, helping navigate the resistance’s underground to help her husband, and making difficult decisions in the name of the cause, and for her to hand her fate over to Rick right at the end is a betrayal of that strength, presumably born out of exhaustion from fighting for so long.

My Original Reading

In my reading, Ilsa doesn’t truly love Rick. I know this is unpopular because, as I said, their final scene is considered one of the most romantic of all time, but I don’t think that Ilsa’s true love in the film is Rick, and, to dig my hole deeper, I don’t think Rick’s is Ilsa. I think that they had the exact type of love they needed in Paris and this is still love, but it is not the type of true love between a husband and wife. And I think Ilsa knew that in Paris and Rick only learned it when she asked him to think for them both.

In Paris, Ilsa was under the impression that her husband had been arrested and murdered by Nazis in a concentration camp. Rick was in exile from his home country for an inexplicable crime and spent at least four years (between the Second Italo-Abyssinian War (1935-37) and the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939)) fighting fascism. Neither was allowed to ask questions of the other. Their love was, in my opinion, a coping mechanism and an escapist fantasy to suspend reality for a bit in the City of Love, a fantasy which we only see in flashback, a suspension of reality in itself. I think that as soon as Ilsa learned that Victor was still alive and waiting for her outside of Paris, she chose to end the fantasy and rejoin her husband, her true love.

So, my reading of the ending is that when Ilsa asks Rick to think for the both of them, she is asking him to think for them; she wants him to realize what she had realized long ago: that Paris is a fantasy that must not interfere with real life. She implores him to think not only about his perspective but also about hers and consider her need for her husband to get to safety so he can continue his vital work. Ultimately, he surprises her by doing just that, and his final speech to her, I think, is what he wishes she had said to him when she left him just a note in Paris. When he then turns to Victor and tells him that Ilsa came to see him the night before to try to convince him that she is still in love with him, Rick says he let her, which I think is a reflection on Paris altogether.

I want to emphasize that I do think Ilsa and Rick have love for each other. I just think it is a specific type of love that humans are capable of, a love that appeals to our survival instincts as social creatures in need of levity and closeness in times otherwise devoid of joy and love. Ultimately, I think my original reading does a disservice to Rick who I think requires Ilsa’s prompting to understand that “we’ll always have Paris” means the escapist fantasy of an uncomplicated love without any of the depth of a love that would ask the other non-native why they’re in Paris in the first place.

Our Reading

Having gotten through the first tapas and made each of our cases for our interpretations, we started adjusting to the other’s perspective. I had not considered Ilsa’s potential as a muse for Victor’s resistance work, and my husband had not considered that Ilsa’s request for him to think for them both could be as multi-layered as in my reading. Neither of us had considered until we began discussing it how significant certain deliveries are in the film. For instance, the only time Ilsa says she loves Rick in Paris is after she knows Victor is alive. She looks away, clearly distraught at Rick’s plans for them to marry in Marseilles knowing she going to leave him, and she says, “I love you so much,” which would be insignificant in any other film, but every single time Victor says he loves his wife, he says “I love you so much.” The precise wording and the fact that she cannot look at Rick as she says it suggests that she may not be saying it to him at all but rather is thinking of Victor and may even be making the decision in that exact moment that she will be returning to her husband.

As another example, Rick also has a specific phrase used to express his love for Ilsa: the most famous catchphrase from the film, “here’s looking at you, Kid.” In talking it through, we came to two conclusions. Firstly, the age difference between the older Rick and the younger Ilsa is probably about 10-12 years, meaning that in Paris, she was likely 23-25 years old, and he was likely 35, because he is at present stated as 37 (to Ilsa’s present 25-27). This means that Ilsa presumed herself widowed in her early 20s. The age difference is discussed multiple times, and my husband and I think that this might be to support the idea that she is the more emotionally mature of the two despite her younger age. A kind of subterfuge suggesting that he is older and therefore wiser that is undercut by the final sequences that show just how much more mature she really is emotionally.

Secondly, the last time he says it is after Ilsa asks him to think for them both, and he says it far more solemnly than any other time in the film. We take this to mean that he is starting to truly see her. All that time in Paris, he was looking at her, but he never truly saw how strong and capable and smart she is until that final recitation with the almost ironic “Kid” dangling at the end as he looks at this passionate, brilliant woman.

All of this is to say that cinema is so fucking important, guys. We got so much out of it on our own, and then, in talking about our ideas and perspectives, my husband and I learned more about each other and ourselves. How beautiful is that? What better Valentine’s Day gift could I ask for than to get to sit and think with my husband? Go watch Casablanca and talk about it with loved ones. I swear it’s healing. Or punch a Nazi. Or maybe both.

Leave a Reply